Xishuangbanna: The Horror, The Horror

After dinner our guide (I am purposefully not using his name here) led us down the dark stairs from the elevated Jinuo shack where we were spending the night, onto the damp, cluttered ground underneath. An annoying dog yapped as we bumbled through the gate in the dark. The sun had set hours before and there was no moon, so we picked our way carefully through the village along a wide muddy path that also served as a toilet. There were no established bathrooms here, except for a decrepit two-holer behind a sheet of corrugated tin near the village schoolyard where we were headed.

But elimination was not our purpose. Instead, the guide promised a taste of dancing and singing with villagers gathering to celebrate the coming lunar New Year. Though tired from the day’s walk, we were anxious to see traditional Jinuo culture emerge from what otherwise seemed a trashy and charm-less village hacked out of the surrounding rubber tree plantations.

We had hired a guide to lead us on this two-day trek that Orchid, an owner of the Mei Mei Cafe—a well known traveler’s hangout in Jinghong—had described as “passing through rice paddies, ethnic villages and jungle.” This combination and the potential for some exercise was appealing after two days of travel from Thailand to Kunming to Jinghong and a couple more days in the city getting re-oriented to life in China. Jinghong itself, though situated in pleasantly hilly country along the Mekong River in the heart of the Xishuangbanna region of southern Yunnan, has little appeal, having succumbed to the fondness of the Chinese for monolithic white tile buildings and blue-tinted glass windows, but it serves as a popular jumping-off point for exploring the area. We were anxious to get out of town. But, we were told, the trek we had hoped to do, south of Jinghong, had recently become a road construction corridor (a fate, we would discover, not unique to one trek).

The guide had moved to Xishuangbanna in the mid-90s to escape the big cities of the north. He and his wife, both worked as tour guides; she for Chinese groups visiting popular urban tourist stops and he mostly for westerners on jungle treks, which paid less but offered the opportunity to indulge his “love of nature.” A thin and twitchy, but kind man, the guide was outspoken and eager to exchange cultural information in English with foreigners. His knowledge of Chinese policy and history was impressive, and he openly criticized government programs, longed for democracy, and was not hesitant to suggest that Mao and his Cultural Revolution had been a disaster for the people of China, a fact widely understood but seldom discussed. Like many Chinese, he felt that ethnic groups in China received preferential treatment, especially financially, and as evidence he pointed to new houses being built in isolated villages along our trek with money provided by the government. “Because of the money,” he told us, “they support the government no matter what they do.” This information was delivered with more than a touch of bitterness.

In the village, the rhythmic pounding of a bass drum penetrated the damp tropical darkness as we neared the schoolyard, where a bare electric bulb dimly illuminated a very strange scene indeed. Hanging horizontally from a metal bar was a large drum that was being whacked energetically by a very drunk, very tiny, very old woman wearing traditional Jinuo clothing and a headlamp, and enthusiastically puffing on a cigarette between beats. With each blow she recoiled as the reverberation traveled up her arms to her tiny, wizened body. Surrounding her were a half dozen similar crones, all smoking or ineffectively trying to light each other’s cigarettes as they convulsed to the beat, chanting like maniacal Druids and downing serial shots of bijou--the local moonshine--poured from a filthy five-gallon plastic Gerry can at the edge of the clearing.

A typical Jinuo imp-lady. This woman supplemented our lunch with nuts and...bijou. While we sipped, she downed 2 or 3 shots.

A smoky fire burned just outside their circle and we crept towards it, trying to remain inconspicuous. The guide, who was friends with the villagers, disappeared immediately, and the rest of us (a young Midwestern couple that had joined us for the trek, along with Ellen and I) crouched nervously at the flickering boundary between light and darkness, hoping we wouldn’t be noticed. Bei, on the other hand, was soon wandering around, blatantly attracting the attention of the dancers.

We were noticed almost immediately, perhaps because of Bei or, more likely, because we were white and twice as tall as the local residents. The rowdy, drunken old women began to drag us, one by one, into their dance circle. Unlike us, Bei succumbed without a struggle and danced energetically, to the hilarity of the ladies. The rest of us, trying pathetically to maintain our dignity, were more dutiful and stiff in our movement which was also noticed, leading to the pouring of large cups of bijou which were then emptied from some distance in the general direction of our mouths by the ancient ones, who by now could barely stand and were cackling uproariously as they simultaneously waved their arms up and down to the rhythm of the drum.

While not tossing bijou in our general direction, the demonic grandmothers also engaged in another ritual that I surmise is not an ancient Jinuo tradition—the stuffing of large, chewy globs of white candy into our mouths with filthy, wrinkled fingers. I looked across the drunken mob towards Ellen, whose eyes said “escape!” as she mimicked the ladies’ arm waving from the center of a tight cluster of bellowing drunks.

I gyrated towards Bei, fending off bijou with limited success—not that bijou is that bad; in fact, sometimes it can be pretty satisfying—but I was afraid that even 100 proof liquor was not enough to kill the filth on the cups. Bei was now a member of a large circle of the dancing elderly, and I feared that she would soon be smoking cigarettes and downing shots with her new friends. To my horror, one of the women lurched towards her, a cup of the clear liquid extended in her claw. I lunged into the group and intercepted the dirty cup just as Bei reached out to accept it, only to discover that it was water and not bijou. In fact, water may have had more long lasting intestinal consequences than a harmless little Dixie cup full of grain alcohol swallowed by a 4-year-old.

Outstretched arms grasped at us, like the Zombies groping through jagged broken windows in “The Return of the Living Dead” as we backed away and made our semi-drunken escape into the muggy night, happy to have gotten away but worried about our digestive systems.

Later that night, as we tossed and turned on thin sleeping mats spread over the hard wooden floor of our sleeping shack, we heard an escalating argument from the hut next door, culminating in screaming, glass breaking and, we learned the next morning, a trip to the hospital for the unfortunate wife involved in alcohol-enhanced domestic violence. We were not sad to pack our packs and hike away the next morning for a day’s walk through miles of rubber plantations to the town of Galanba, where we enjoyed an oily lunch before catching a bus back to Jinghong.

Though amusing in hindsight, the entire Xishuangbanna experience for us signaled our low-water-mark in China, brought on by culture fatigue, enhanced by the contrast with what had been relatively easy traveling (and good food) in Thailand, and exacerbated by the fact that the Xishuangbanna that we saw was, despite its reputation, a trashy combination of tacky tourist sites, vigorous road construction and monotonous rubber plantations occupying every square meter of what had once been pristine tropical forest. Even the Han Chinese who once flocked to the area during their holidays had abandoned ship, and once thriving hotels now deteriorated into filthy dives.

The trek, which we had hoped would improve our attitudes, was a disappointment too, though the Jinuo ladies injected some interest. Ironically, given the guide's “love of nature,” the first walking day he had unapologetically taken us directly along an active road construction corridor where workers are building what will eventually be a superhighway from Bangkok to China, via Laos. We walked for miles through what amounted to interstate highway construction, sometimes climbing over rebar infested concrete or traversing around piles of gravel and sand. Finally escaping the construction, we made token forays into tiny patches of hammered jungle, all that remained in the sea of rubber plantations, before finally descending into the alcoholic Jinuo village.

Hiking through road construction on the first day of our "jungle trek." The horror.

The day after returning to Jinghong we bought plane tickets back to Lijiang where, after regrouping for a couple of days, we headed north into the mountains along the Yangze and Mekong rivers for two treks that would rekindle our love for Yunnan and wash away our fatigue. I think in the end we were just hungry to escape big cities, after traveling through Bangkok, Chiang Mai, Kunming and Jinghong. And we were hungry to find places that felt peaceful and ancient. China is developing so fast that remote country disappears almost before you can find it. I’m sure that Xishuangbanna has beautiful treks to offer, and the people are inarguably interesting, but our patience wore too thin to search further.

It’s often the mountains that pull you back.

Around the city of Jinghong and within the Mekong River valley, all flat land has been divided into rice fields and plots for other crops. The surrounding mountains are planted in rubber trees, which are quite profitable for their owners.

The agricultural Mekong River valley gives way to mountains that extend southward into Laos.

Bei enjoys some hashbrowns at the Mekong Cafe in Jinghong, where we had lunch upon our arrival and tried to sort out where we should trek.

The Ace Hardware of China. Stands like this are common in every city I've visited, and the proprietors can do anything from fixing flat bike tires to making keys.

In Jinghong, a night market occupies a seedy area along the Mekong. BBQ is abundant. You choose your kabobs and they are thrown on the grill for you.

The Mekong night market beckons. Restaurants, a second-rate carnival, and a series of seedy bars lit the tropical night on the edge of Jinghong.

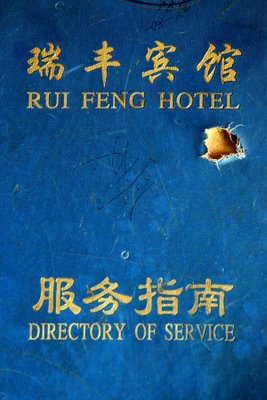

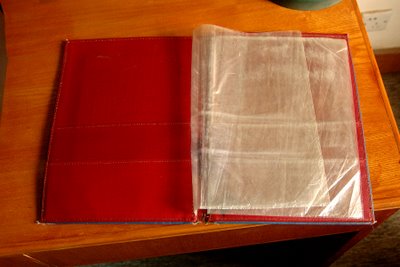

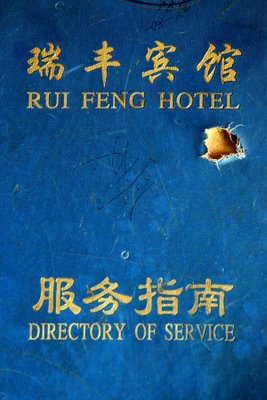

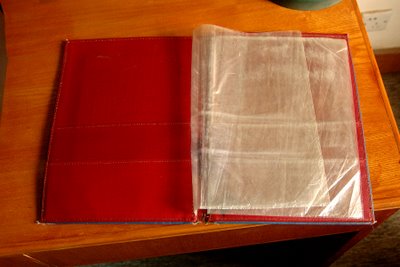

Our venerable Lonely Planet guide described the Rui Feng Hotel as "modern" with "spotless, carpeted rooms with nice bathrooms." This was hands down the most disgusting dive I've ever stayed in. The bathroom door was rotting, the "spotless carpet" was wet and filthy, and we spent an uncomfortable night trying not to touch anything with our bare skin. This "Directory of Service" shown here and then opened in the following picture, says it all.

A pretty accurate list of services at the Rui Feng Hotel in Jinghong.

We spent the Chinese New Year in Jinghong. On the streets, there were many red things for sale, and on New Year's night, we were bombarded by the continuous explosions of some of the loudest fireworks I've ever heard. The noise was accentuated and amplified as it echoed down the canyons of tile buildings that line the streets of the city. The following day, the streets were littered with bomb debris and I saw more than a few locals wearing fresh bandages.

A bird (chicken) market in Jinghong.

Bei and Ellen on a rented bicycle exploring the countryside near Jinghong.

A village house along our trek. The house in the foreground is "shingled" with the lids from 55-gallon drums.

A palm.

Drum sticks at a temple near Jinghong. The sticks the Jinuo women used to beat their drum were considerably less refined than these, but just as effective.

Ladies avoiding the hot sun in a village near Jinghong.

Market goods in Jinghong.

This guy, crouching in a Jinghong market, was not drinking water.

The sign at the Jinghong bus station sums up traveling by bus in China. We took some short bus rides to nearby towns.

A bus driver lashes a bike to the top of his rig. In Xishuangbanna, you can rent bicycles and then take buses to good riding areas.

This kid, in a primitive village along our treking route, was remarkably good at hauling ass through cluttered village streets on this bike that was several sizes too big for him.

A storage shed in a village along our treking route where we stopped for lunch. The long boxes stored underneath the shack are coffins. And the things piled in front of them are asbestos shingles. Coincidence?

A lady gets water in a typical village on our trek.

Bei enjoys a selection of lunch items on the first treking day.

This little guy avoiding becoming lunch. His day will come.

Rubber trees in the hills near Jinghong.

A little Thailand nostalgia? Perhaps.

But elimination was not our purpose. Instead, the guide promised a taste of dancing and singing with villagers gathering to celebrate the coming lunar New Year. Though tired from the day’s walk, we were anxious to see traditional Jinuo culture emerge from what otherwise seemed a trashy and charm-less village hacked out of the surrounding rubber tree plantations.

We had hired a guide to lead us on this two-day trek that Orchid, an owner of the Mei Mei Cafe—a well known traveler’s hangout in Jinghong—had described as “passing through rice paddies, ethnic villages and jungle.” This combination and the potential for some exercise was appealing after two days of travel from Thailand to Kunming to Jinghong and a couple more days in the city getting re-oriented to life in China. Jinghong itself, though situated in pleasantly hilly country along the Mekong River in the heart of the Xishuangbanna region of southern Yunnan, has little appeal, having succumbed to the fondness of the Chinese for monolithic white tile buildings and blue-tinted glass windows, but it serves as a popular jumping-off point for exploring the area. We were anxious to get out of town. But, we were told, the trek we had hoped to do, south of Jinghong, had recently become a road construction corridor (a fate, we would discover, not unique to one trek).

The guide had moved to Xishuangbanna in the mid-90s to escape the big cities of the north. He and his wife, both worked as tour guides; she for Chinese groups visiting popular urban tourist stops and he mostly for westerners on jungle treks, which paid less but offered the opportunity to indulge his “love of nature.” A thin and twitchy, but kind man, the guide was outspoken and eager to exchange cultural information in English with foreigners. His knowledge of Chinese policy and history was impressive, and he openly criticized government programs, longed for democracy, and was not hesitant to suggest that Mao and his Cultural Revolution had been a disaster for the people of China, a fact widely understood but seldom discussed. Like many Chinese, he felt that ethnic groups in China received preferential treatment, especially financially, and as evidence he pointed to new houses being built in isolated villages along our trek with money provided by the government. “Because of the money,” he told us, “they support the government no matter what they do.” This information was delivered with more than a touch of bitterness.

In the village, the rhythmic pounding of a bass drum penetrated the damp tropical darkness as we neared the schoolyard, where a bare electric bulb dimly illuminated a very strange scene indeed. Hanging horizontally from a metal bar was a large drum that was being whacked energetically by a very drunk, very tiny, very old woman wearing traditional Jinuo clothing and a headlamp, and enthusiastically puffing on a cigarette between beats. With each blow she recoiled as the reverberation traveled up her arms to her tiny, wizened body. Surrounding her were a half dozen similar crones, all smoking or ineffectively trying to light each other’s cigarettes as they convulsed to the beat, chanting like maniacal Druids and downing serial shots of bijou--the local moonshine--poured from a filthy five-gallon plastic Gerry can at the edge of the clearing.

A typical Jinuo imp-lady. This woman supplemented our lunch with nuts and...bijou. While we sipped, she downed 2 or 3 shots.

A smoky fire burned just outside their circle and we crept towards it, trying to remain inconspicuous. The guide, who was friends with the villagers, disappeared immediately, and the rest of us (a young Midwestern couple that had joined us for the trek, along with Ellen and I) crouched nervously at the flickering boundary between light and darkness, hoping we wouldn’t be noticed. Bei, on the other hand, was soon wandering around, blatantly attracting the attention of the dancers.

We were noticed almost immediately, perhaps because of Bei or, more likely, because we were white and twice as tall as the local residents. The rowdy, drunken old women began to drag us, one by one, into their dance circle. Unlike us, Bei succumbed without a struggle and danced energetically, to the hilarity of the ladies. The rest of us, trying pathetically to maintain our dignity, were more dutiful and stiff in our movement which was also noticed, leading to the pouring of large cups of bijou which were then emptied from some distance in the general direction of our mouths by the ancient ones, who by now could barely stand and were cackling uproariously as they simultaneously waved their arms up and down to the rhythm of the drum.

While not tossing bijou in our general direction, the demonic grandmothers also engaged in another ritual that I surmise is not an ancient Jinuo tradition—the stuffing of large, chewy globs of white candy into our mouths with filthy, wrinkled fingers. I looked across the drunken mob towards Ellen, whose eyes said “escape!” as she mimicked the ladies’ arm waving from the center of a tight cluster of bellowing drunks.

I gyrated towards Bei, fending off bijou with limited success—not that bijou is that bad; in fact, sometimes it can be pretty satisfying—but I was afraid that even 100 proof liquor was not enough to kill the filth on the cups. Bei was now a member of a large circle of the dancing elderly, and I feared that she would soon be smoking cigarettes and downing shots with her new friends. To my horror, one of the women lurched towards her, a cup of the clear liquid extended in her claw. I lunged into the group and intercepted the dirty cup just as Bei reached out to accept it, only to discover that it was water and not bijou. In fact, water may have had more long lasting intestinal consequences than a harmless little Dixie cup full of grain alcohol swallowed by a 4-year-old.

Outstretched arms grasped at us, like the Zombies groping through jagged broken windows in “The Return of the Living Dead” as we backed away and made our semi-drunken escape into the muggy night, happy to have gotten away but worried about our digestive systems.

Later that night, as we tossed and turned on thin sleeping mats spread over the hard wooden floor of our sleeping shack, we heard an escalating argument from the hut next door, culminating in screaming, glass breaking and, we learned the next morning, a trip to the hospital for the unfortunate wife involved in alcohol-enhanced domestic violence. We were not sad to pack our packs and hike away the next morning for a day’s walk through miles of rubber plantations to the town of Galanba, where we enjoyed an oily lunch before catching a bus back to Jinghong.

Though amusing in hindsight, the entire Xishuangbanna experience for us signaled our low-water-mark in China, brought on by culture fatigue, enhanced by the contrast with what had been relatively easy traveling (and good food) in Thailand, and exacerbated by the fact that the Xishuangbanna that we saw was, despite its reputation, a trashy combination of tacky tourist sites, vigorous road construction and monotonous rubber plantations occupying every square meter of what had once been pristine tropical forest. Even the Han Chinese who once flocked to the area during their holidays had abandoned ship, and once thriving hotels now deteriorated into filthy dives.

The trek, which we had hoped would improve our attitudes, was a disappointment too, though the Jinuo ladies injected some interest. Ironically, given the guide's “love of nature,” the first walking day he had unapologetically taken us directly along an active road construction corridor where workers are building what will eventually be a superhighway from Bangkok to China, via Laos. We walked for miles through what amounted to interstate highway construction, sometimes climbing over rebar infested concrete or traversing around piles of gravel and sand. Finally escaping the construction, we made token forays into tiny patches of hammered jungle, all that remained in the sea of rubber plantations, before finally descending into the alcoholic Jinuo village.

Hiking through road construction on the first day of our "jungle trek." The horror.

The day after returning to Jinghong we bought plane tickets back to Lijiang where, after regrouping for a couple of days, we headed north into the mountains along the Yangze and Mekong rivers for two treks that would rekindle our love for Yunnan and wash away our fatigue. I think in the end we were just hungry to escape big cities, after traveling through Bangkok, Chiang Mai, Kunming and Jinghong. And we were hungry to find places that felt peaceful and ancient. China is developing so fast that remote country disappears almost before you can find it. I’m sure that Xishuangbanna has beautiful treks to offer, and the people are inarguably interesting, but our patience wore too thin to search further.

It’s often the mountains that pull you back.

Around the city of Jinghong and within the Mekong River valley, all flat land has been divided into rice fields and plots for other crops. The surrounding mountains are planted in rubber trees, which are quite profitable for their owners.

The agricultural Mekong River valley gives way to mountains that extend southward into Laos.

Bei enjoys some hashbrowns at the Mekong Cafe in Jinghong, where we had lunch upon our arrival and tried to sort out where we should trek.

The Ace Hardware of China. Stands like this are common in every city I've visited, and the proprietors can do anything from fixing flat bike tires to making keys.

In Jinghong, a night market occupies a seedy area along the Mekong. BBQ is abundant. You choose your kabobs and they are thrown on the grill for you.

The Mekong night market beckons. Restaurants, a second-rate carnival, and a series of seedy bars lit the tropical night on the edge of Jinghong.

Our venerable Lonely Planet guide described the Rui Feng Hotel as "modern" with "spotless, carpeted rooms with nice bathrooms." This was hands down the most disgusting dive I've ever stayed in. The bathroom door was rotting, the "spotless carpet" was wet and filthy, and we spent an uncomfortable night trying not to touch anything with our bare skin. This "Directory of Service" shown here and then opened in the following picture, says it all.

A pretty accurate list of services at the Rui Feng Hotel in Jinghong.

We spent the Chinese New Year in Jinghong. On the streets, there were many red things for sale, and on New Year's night, we were bombarded by the continuous explosions of some of the loudest fireworks I've ever heard. The noise was accentuated and amplified as it echoed down the canyons of tile buildings that line the streets of the city. The following day, the streets were littered with bomb debris and I saw more than a few locals wearing fresh bandages.

A bird (chicken) market in Jinghong.

Bei and Ellen on a rented bicycle exploring the countryside near Jinghong.

A village house along our trek. The house in the foreground is "shingled" with the lids from 55-gallon drums.

A palm.

Drum sticks at a temple near Jinghong. The sticks the Jinuo women used to beat their drum were considerably less refined than these, but just as effective.

Ladies avoiding the hot sun in a village near Jinghong.

Market goods in Jinghong.

This guy, crouching in a Jinghong market, was not drinking water.

The sign at the Jinghong bus station sums up traveling by bus in China. We took some short bus rides to nearby towns.

A bus driver lashes a bike to the top of his rig. In Xishuangbanna, you can rent bicycles and then take buses to good riding areas.

This kid, in a primitive village along our treking route, was remarkably good at hauling ass through cluttered village streets on this bike that was several sizes too big for him.

A storage shed in a village along our treking route where we stopped for lunch. The long boxes stored underneath the shack are coffins. And the things piled in front of them are asbestos shingles. Coincidence?

A lady gets water in a typical village on our trek.

Bei enjoys a selection of lunch items on the first treking day.

This little guy avoiding becoming lunch. His day will come.

Rubber trees in the hills near Jinghong.

A little Thailand nostalgia? Perhaps.

6 Comments:

I found this blog by coincidence, when I looked for information about Jinghong. While this entry is quite old, I still wanted to ask you to maybe remove those comments about the guide. I don't believe it's fair to publicly mention what he thinks about the situation in China. It won't be to your guide's and his family's advantage. Hopefully any Chinese organizations would just assume that he just wanted to humour foreign tourists or that you misunderstood his opinions, but I'd still like to urge you to remove these comments.

Dear "comment from Germany." I see your point, and certainly did not intend to cause any harm to the guide, who was excellent. This blog is so old that I'm having trouble finding a way to access and edit it to make more generic, but I will continue to try to figure out how. Thanks for being thoughtful about this.

Changes made...

I came across this blog hoping to find information on trekking around Xishuangbanna! I've just read your description of trying to "escape!" from a "drunken mob" full of "demonic," "rowdy, drunken" women (aka "bellowing drunks") with "claws," "filthy, wrinkled fingers," "lurching" towards you like "zombies groping through jagged broken windows in "The Return of the Living Dead." Hm. I wonder, could it be that they were just offering you candy, liquor and an invitation to the party that you had just "gyrated" into unannounced (from your "hiding spot" on the "flickering boundary between light and darkness") and, perhaps, that you are just racist? Is it really amusing only in hindsight; not even a little fun at the time? Did nothing cultural emerge from the trashy and charm-less village?

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

I'm re-replying here to correct an error in my previous comment. First, I abhor racism, so I take a comment like yours seriously, but I don't see how this post has anything to do with race. It's a description of what for us was a not especially fun evening at a drunken party that went late into the night. I hope you have a great experience in Xishuangbanna. People there were very kind to us, but this trek was not great for a variety of reasons.

Post a Comment

<< Home