Three Weddings and a Funeral

In the prelude to his ballad “Better Off Without a Wife”, Tom Waits describes a not-so-blushing bride-to-be: “She’s been married so many times she has rice marks all over her face.”

Waits would have been right at home at the third wedding in less than a year for our waiban (foreign teacher handler) Ren Jing, the ultra-petite woman at our college who does everything from arranging our schedules to negotiating our work permits with the PSB to helping us with required and gripping medical exams at the Lijiang hospital to inducing a Pavlovian dread of her phone calls, which inevitably call for some unpleasant bureaucratic response—usually quickly. And she teaches English.

It’s a wonder she has time for all of those weddings.

But those of you inclined to pass judgment on this sort of thing should not be too hasty. All of Ren Jing’s weddings were to the same man, and as Ellen, Bei and I approached the doorway of the three-star Lijiang hotel where the day’s festivities would take place he stood, along with his very put-together and significantly air-brushed bride, holding a large silver platter draped with a red cloth and piled high with Chinese filter cigarettes.

Ren Jing and her husband greet guests with candy and cigarettes.

In America, the stress of just thinking about a wedding was enough to send Ellen and me quietly to the Laramie (Wyoming) Justice of the Peace, who was duty-bound to perform our nuptials with little fanfare. Not that we are typical. In more extroverted American social circles, the parents of the bride meet nervously with their financial planners to decide which assets to liquidate before hosting their daughter’s one (they hope) special day.

But in China, just one wedding is sometimes not enough. And in fact, weddings here may be self-sustaining—at Ren Jing’s 3rd wedding—the one we attended—arriving guests were unashamedly asked to produce red envelopes, traditionally enclosing at least 50 yuan per guest—a tidy sum in China. Body language and instructions from the envelope collectors, arrayed like well-dressed body guards near the cigarette-wielding groom, translated roughly to: “Do you have an envelope??!! Give it to us now or go home.”

We produce our envelope.

One thing that you can say about weddings in China if the one we attended was typical is that once in the door the celebrations are pretty sane—more so than many of their counterparts in the U.S., where endless toasts can go for hours, couples who should not be allowed near a typewriter recite their self-authored vows, and aging schmaltz-bands force horrified attendees onto the dance floor to devise jerky reactions to un-danceable mus-ak. At Ren Jing’s 3rd, we were in and out the door in less than 2 hours, stomachs full and dignity mostly intact.

Bei acknowledges the bride and groom.

The Chinese equivalent of the garter toss. Whoever catches the rose gets...thorns...and according to tradition, is likely to marry within a year.

Bei's-eye view of the wedding dinner. Photo credit: Bei Driese

The feast: a rooster with comb intact...

...and fish.

And before I move on, you must be wondering WHY Ren Jing had three weddings. The answer is simple: once for family, once for friends and, as Ren Jing would put it in her pretty good English, once for my colleag – gahs at the college.

The view from Wenhai toward Jade Dragon Snow Mountain (Yulong Xueshan).

A few weeks later we found ourselves attending a funeral in the small Naxi village of Wenhai. “What,” you ask, “is the connection between a wedding in Lijiang and a funeral in a small village on the flanks of the Jade Dragon Snow Mountain?” It’s tenuous, but has to do with those filter cigarettes; this time walked around in a large basin to all of the men at the post-funeral dinner, much as a good New York host would deliver little bits foie gras or flutes of champagne. Cigarettes at a funeral—as if to insure that the deceased does not suffer alone for long the netherworld without the company of her male friends and family (few women smoke).

Cigarettes are part of the culture here and were handed out at both the wedding and the funeral. This man unabashedly enjoyed his.

A local man at the wake, cigarette in hand.

We became peripherally involved in the Naxi funeral by chance during a return trip to the Wenhai Ecolodge, where we have spent a few weekends in the past 8 months and where we traveled on this weekend to see the now blooming rhododendrons. A 57-year-old woman, who had lived in a house adjacent to the lodge, died of a chronic heart problem during the week before our arrival, reportedly while she worked in the fields. As we walked by her house on our arrival, we noticed a big dinner party in the courtyard, along with what Ellen thought looked like some guys building a boat (which of course turned out to be the coffin) but we gave it little thought, tired from our walk and assuming it was just a local get-together.

Rhododendrons along the trail from the valley to Wenhai. The mountains are thick with blooms right now.

Rhododendron blossoms.

Later, Bei reported to us, after returning from the dead woman’s house where she had been whisked by a covey of local women (to eat and play): “There were two people in bed there. And one of them was dead and the other one was crying.” She went on: “the dead woman was beautiful—she was wearing makeup.”

“Was the other woman dying?” Ellen asked (momentary visions of a bird flu outbreak fluttered through our heads).

“Maybe,” Bei replied, unperturbed, before running off to explore the Ecolodge and to invent fairy princesses to occupy its nooks and crannies.

Ellen and I looked at each other for a moment and then got the rest of the story in bits and pieces from villagers who work at the communally-run lodge. And we agreed that this was a good way for Bei to see death—something that in our society is held much more at arm’s length and regarded with much more fear and secrecy than it is here.

As it turned out, the other bed-ridden woman was a mourning relative and was not, in fact, dying. (Pass the chicken, please.)

I can offer little insight into the personal stories around the life of the dead woman and her family, since I don’t speak much Chinese, let alone Naxi, the language of the village. The locals were kind to include us in their eating and to invite us to watch the funeral procession, but we stayed mostly on the periphery, respectful of the passing of someone who had spent their life in this tiny community, and feeling like the superficial visitors that we were. But that weekend, as I enjoyed the beauty of the place—the quiet of the village, where kids still run home from school on dirt tracks; the aging herders, who still move their cows from adobe brick houses onto the broad meadow surrounding the ephemeral Wenhai Lake; the people at the banquet, laugh lines permanently etched by the sun at the corners of their eyes—I thought about what it would be like to be born, raised, and married; to raise children and to die, all with this place as the backdrop of your life.

How many more generations of people will spend their lives in such a simple way, sheltered from the rush of change that is sweeping over China? As we left Wenhai on Sunday afternoon, Bei on a horse for the 3-hour walk back to Shuhe, acquaintances of the family also left to return home, most to their houses in the village, but some in cars or on motorcycles, driving down the new dirt road connecting the village to the Lijiang valley where they now make their homes.

Kids running home from school on the weekend of the funeral.

An old woman watches as her not-so-young son (I'm guessing it's her son) takes cattle out into the meadows at Wenhai. What changes has she seen in a lifetime at Wenhai?

Horses graze in the beautiful green meadows around Wenhai Lake. At the end of the rainy season, these will be underwater, but during the dry season the lake shrinks and reveals perfect grazing for the village herds.

A shepherd along the shore of the now shrunken Wenhai Lake.

A Wenhai woman, etched by the sun.

A fence enclosing yellow blossoms at Wenhai.

Bei and one of her peers get acquainted.

Spring foliage and trees near the fields surrounding Wenhai.

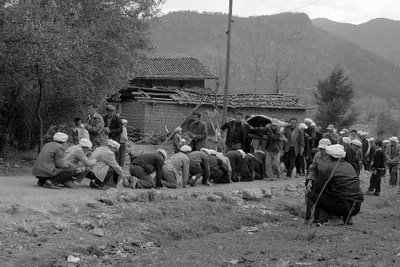

The funeral. Family of the deceased woman wear white cloth wrapped around their heads. The men of the family line up and kowtow in anticipation of the journey of the coffin to the cemetary.

A new generation watches the passing of one of their family members. Will these boys live out their lives at Wenhai, or will they leave to seek a more compex life?

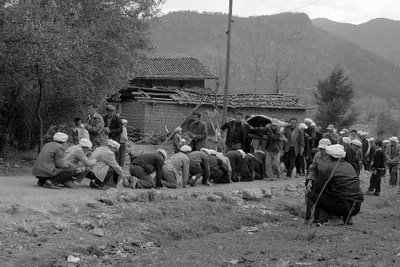

The coffin is passed over the heads of the men of the family.

Men carrying the coffin over the heads of family members. Note the cigarette. All of the funeral attendees follow the coffin up past the house and to the edge of the fields, where they bid goodbye to the deceased woman. Then the men continue on to the graveyard where they bury the woman. The rest of the people return to the house for a big meal, to be joined by the coffin bearers later.

A typical (old) grave at Wenhai. Newer graves are adorned with more elaborate monuments.

A boy from the dead womans family pushes his bike in front of the family house.

The gathering at the dead woman's house.

Two generations at Wenhai--a mom and her baby.

East meets west -- Bei with one of the local boys.

A boy from the dead woman's family wearing the traditional white wrap.

A girl at the post-funeral dinner.

Although living in a village about 5 miles from Wenhai, these Yi women probably attended school with Naxi kids from Wenhai. While walking to this Yi village, I passed an old woman walking towards Wenhai. On my return, I passed her coming back with about 10 kids who had spent their school week living at Wenhai and were on their way home for the weekend.

A man and a baby rest on the grass outside the house where the funeral dinner was finishing up.

Bei and Ellen talking with some of the Naxi villagers after the funeral.

We left Wenhai to return to our world--Bei on her horse and us on foot. The growing city of Lijiang occupies the valley in the background. Lijiang tourism and economic growth is quickly encroaching on previously isolated places like Wenhai.

Locals heading home from the funeral. Most are on foot, but a few friends from the valley leave in cars or on motorbikes to drive down the road, recently carved up the mountainside to connect Wenhai to the valley town of Baisha. Locals I asked say that they like having the road there. It makes life easier. But what will this quiet place be like in 20 years? Maybe the woman that died is part of the last generation to live a traditional life at Wenhai.

Waits would have been right at home at the third wedding in less than a year for our waiban (foreign teacher handler) Ren Jing, the ultra-petite woman at our college who does everything from arranging our schedules to negotiating our work permits with the PSB to helping us with required and gripping medical exams at the Lijiang hospital to inducing a Pavlovian dread of her phone calls, which inevitably call for some unpleasant bureaucratic response—usually quickly. And she teaches English.

It’s a wonder she has time for all of those weddings.

But those of you inclined to pass judgment on this sort of thing should not be too hasty. All of Ren Jing’s weddings were to the same man, and as Ellen, Bei and I approached the doorway of the three-star Lijiang hotel where the day’s festivities would take place he stood, along with his very put-together and significantly air-brushed bride, holding a large silver platter draped with a red cloth and piled high with Chinese filter cigarettes.

Ren Jing and her husband greet guests with candy and cigarettes.

In America, the stress of just thinking about a wedding was enough to send Ellen and me quietly to the Laramie (Wyoming) Justice of the Peace, who was duty-bound to perform our nuptials with little fanfare. Not that we are typical. In more extroverted American social circles, the parents of the bride meet nervously with their financial planners to decide which assets to liquidate before hosting their daughter’s one (they hope) special day.

But in China, just one wedding is sometimes not enough. And in fact, weddings here may be self-sustaining—at Ren Jing’s 3rd wedding—the one we attended—arriving guests were unashamedly asked to produce red envelopes, traditionally enclosing at least 50 yuan per guest—a tidy sum in China. Body language and instructions from the envelope collectors, arrayed like well-dressed body guards near the cigarette-wielding groom, translated roughly to: “Do you have an envelope??!! Give it to us now or go home.”

We produce our envelope.

One thing that you can say about weddings in China if the one we attended was typical is that once in the door the celebrations are pretty sane—more so than many of their counterparts in the U.S., where endless toasts can go for hours, couples who should not be allowed near a typewriter recite their self-authored vows, and aging schmaltz-bands force horrified attendees onto the dance floor to devise jerky reactions to un-danceable mus-ak. At Ren Jing’s 3rd, we were in and out the door in less than 2 hours, stomachs full and dignity mostly intact.

Bei acknowledges the bride and groom.

The Chinese equivalent of the garter toss. Whoever catches the rose gets...thorns...and according to tradition, is likely to marry within a year.

Bei's-eye view of the wedding dinner. Photo credit: Bei Driese

The feast: a rooster with comb intact...

...and fish.

And before I move on, you must be wondering WHY Ren Jing had three weddings. The answer is simple: once for family, once for friends and, as Ren Jing would put it in her pretty good English, once for my colleag – gahs at the college.

The view from Wenhai toward Jade Dragon Snow Mountain (Yulong Xueshan).

A few weeks later we found ourselves attending a funeral in the small Naxi village of Wenhai. “What,” you ask, “is the connection between a wedding in Lijiang and a funeral in a small village on the flanks of the Jade Dragon Snow Mountain?” It’s tenuous, but has to do with those filter cigarettes; this time walked around in a large basin to all of the men at the post-funeral dinner, much as a good New York host would deliver little bits foie gras or flutes of champagne. Cigarettes at a funeral—as if to insure that the deceased does not suffer alone for long the netherworld without the company of her male friends and family (few women smoke).

Cigarettes are part of the culture here and were handed out at both the wedding and the funeral. This man unabashedly enjoyed his.

A local man at the wake, cigarette in hand.

We became peripherally involved in the Naxi funeral by chance during a return trip to the Wenhai Ecolodge, where we have spent a few weekends in the past 8 months and where we traveled on this weekend to see the now blooming rhododendrons. A 57-year-old woman, who had lived in a house adjacent to the lodge, died of a chronic heart problem during the week before our arrival, reportedly while she worked in the fields. As we walked by her house on our arrival, we noticed a big dinner party in the courtyard, along with what Ellen thought looked like some guys building a boat (which of course turned out to be the coffin) but we gave it little thought, tired from our walk and assuming it was just a local get-together.

Rhododendrons along the trail from the valley to Wenhai. The mountains are thick with blooms right now.

Rhododendron blossoms.

Later, Bei reported to us, after returning from the dead woman’s house where she had been whisked by a covey of local women (to eat and play): “There were two people in bed there. And one of them was dead and the other one was crying.” She went on: “the dead woman was beautiful—she was wearing makeup.”

“Was the other woman dying?” Ellen asked (momentary visions of a bird flu outbreak fluttered through our heads).

“Maybe,” Bei replied, unperturbed, before running off to explore the Ecolodge and to invent fairy princesses to occupy its nooks and crannies.

Ellen and I looked at each other for a moment and then got the rest of the story in bits and pieces from villagers who work at the communally-run lodge. And we agreed that this was a good way for Bei to see death—something that in our society is held much more at arm’s length and regarded with much more fear and secrecy than it is here.

As it turned out, the other bed-ridden woman was a mourning relative and was not, in fact, dying. (Pass the chicken, please.)

I can offer little insight into the personal stories around the life of the dead woman and her family, since I don’t speak much Chinese, let alone Naxi, the language of the village. The locals were kind to include us in their eating and to invite us to watch the funeral procession, but we stayed mostly on the periphery, respectful of the passing of someone who had spent their life in this tiny community, and feeling like the superficial visitors that we were. But that weekend, as I enjoyed the beauty of the place—the quiet of the village, where kids still run home from school on dirt tracks; the aging herders, who still move their cows from adobe brick houses onto the broad meadow surrounding the ephemeral Wenhai Lake; the people at the banquet, laugh lines permanently etched by the sun at the corners of their eyes—I thought about what it would be like to be born, raised, and married; to raise children and to die, all with this place as the backdrop of your life.

How many more generations of people will spend their lives in such a simple way, sheltered from the rush of change that is sweeping over China? As we left Wenhai on Sunday afternoon, Bei on a horse for the 3-hour walk back to Shuhe, acquaintances of the family also left to return home, most to their houses in the village, but some in cars or on motorcycles, driving down the new dirt road connecting the village to the Lijiang valley where they now make their homes.

Kids running home from school on the weekend of the funeral.

An old woman watches as her not-so-young son (I'm guessing it's her son) takes cattle out into the meadows at Wenhai. What changes has she seen in a lifetime at Wenhai?

Horses graze in the beautiful green meadows around Wenhai Lake. At the end of the rainy season, these will be underwater, but during the dry season the lake shrinks and reveals perfect grazing for the village herds.

A shepherd along the shore of the now shrunken Wenhai Lake.

A Wenhai woman, etched by the sun.

A fence enclosing yellow blossoms at Wenhai.

Bei and one of her peers get acquainted.

Spring foliage and trees near the fields surrounding Wenhai.

The funeral. Family of the deceased woman wear white cloth wrapped around their heads. The men of the family line up and kowtow in anticipation of the journey of the coffin to the cemetary.

A new generation watches the passing of one of their family members. Will these boys live out their lives at Wenhai, or will they leave to seek a more compex life?

The coffin is passed over the heads of the men of the family.

Men carrying the coffin over the heads of family members. Note the cigarette. All of the funeral attendees follow the coffin up past the house and to the edge of the fields, where they bid goodbye to the deceased woman. Then the men continue on to the graveyard where they bury the woman. The rest of the people return to the house for a big meal, to be joined by the coffin bearers later.

A typical (old) grave at Wenhai. Newer graves are adorned with more elaborate monuments.

A boy from the dead womans family pushes his bike in front of the family house.

The gathering at the dead woman's house.

Two generations at Wenhai--a mom and her baby.

East meets west -- Bei with one of the local boys.

A boy from the dead woman's family wearing the traditional white wrap.

A girl at the post-funeral dinner.

Although living in a village about 5 miles from Wenhai, these Yi women probably attended school with Naxi kids from Wenhai. While walking to this Yi village, I passed an old woman walking towards Wenhai. On my return, I passed her coming back with about 10 kids who had spent their school week living at Wenhai and were on their way home for the weekend.

A man and a baby rest on the grass outside the house where the funeral dinner was finishing up.

Bei and Ellen talking with some of the Naxi villagers after the funeral.

We left Wenhai to return to our world--Bei on her horse and us on foot. The growing city of Lijiang occupies the valley in the background. Lijiang tourism and economic growth is quickly encroaching on previously isolated places like Wenhai.

Locals heading home from the funeral. Most are on foot, but a few friends from the valley leave in cars or on motorbikes to drive down the road, recently carved up the mountainside to connect Wenhai to the valley town of Baisha. Locals I asked say that they like having the road there. It makes life easier. But what will this quiet place be like in 20 years? Maybe the woman that died is part of the last generation to live a traditional life at Wenhai.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home