Commuting

Ellen doesn’t love my favorite 30-minute bicycle commute from Gu Cheng(Old Town) to the da xue (college). It has to do with her aversion to dust—dust that settles into your hair and sticks to your teeth as you bounce along through road construction behind a wheezing dump truck. But for me, the alternative route up the well-maintained but less direct Shangrila Lu adds minutes to my trip which I usually don’t have to spare, and offers less interesting, though by no means boring, sights. So several times a week, I eat dust and Ellen pedals on the pavement.

Ellen's preferred route follows Shangrila Street from town out to the school. The views are not too bad and the road is not devoid of cultural interest either.

"Stick" tree plantings along the Shangrila route to school. Ellen is flabbergasted that these miserable sticks, stuffed into the ground and given minimal water, eventually thrive and become trees. But it's true.

Our commute doesn't leave us looking quite a clean and perky as this shampoo model on a billboard in Lijiang.

To put this into perspective I should say that we’re already beginning to grieve (not too strong a word) our late July departure from this extraordinary place. It isn’t just the trips we’ve taken that we’ll miss. It’s also daily life; the glimpses of things simultaneously insignificant and remarkable. These glimpses will be remembered as fondly as sunrises on big mountains or shadows settling along the Yangze. The 30-minute bicycle commute each day is part of our mental landscape and on almost every ride, I see something that I want to remember.

Images like this are part of every day and every trip out of the house.

A typical teaching day for us begins at about 6:00 a.m. when we open our eyes and, from under the heavy comforter on our cobbled-together but comfortable bed (foam mattresses atop roughcut boards resting precariously on stacks of bricks constrained within a dilapidated frame), have a look through open louver doors into the courtyard, still in shadow, and to the sky, just growing light. If we sleep a little late the sun wakes us up, reflecting off the chrome tank that feeds the solar hot water heater which on a sunny day will produce plenty of water for dribbling gravity-fed showers. But we don’t worry as much about hygiene here as we do in the States, and showers can usually wait for hot afternoons, when the breeze that filters through the mostly open cinder-block bathroom doesn’t seem so daunting.

The courtyard of our house in Old Town. The pebble surface makes for wobbly trips to the bathroom in the middle of the night but it is a nice place to wake up in the morning.

Our solar hot water heater. "China's best brand" according to the decal.

Living in a courtyard house is a little like camping out. There is no heat unless you huddle around an electric space heater, light a charcoal fire in a brazier or leave the kitchen gas burners on a little longer than necessary after boiling water for coffee. But it’s almost summer now and mornings are warm—so the barefoot hobble across the pebble-paved courtyard to the bathroom is not so bad. And at night, from our bed, we can see the stars.

I get up and get dressed, putting on one of my two “nice” teaching shirts and a pair of Levi’s—all now threadbare after 8 months, but still more appropriate than showing up to teach in a t-shirt. When we leave China the shirts will be left behind, along with much of the flotsam we inveterate American consumers have accumulated here—pots and pans, pressure cooker, DVD player, stacks of pirated DVDs, English novels, day packs, bikes and our now rarely used electric space heater.

In the kitchen, I brew a cup of Yunnan coffee—spooned into my coffee filter from a plastic ice cream container that once every couple of weeks I get refilled at a local cafe for 40 yuan (about $5). The coffee isn’t bad, and it’s a lot better when I have real cream than when condensed milk is my only option. The cream comes from Kunming (10 hours away) via another cafe (The Prague) that orders it for us, and it’s a luxury that improves my morning immeasurably.

Bei in the kitchen. We have a two burner gas stove which doubles as a heat source on cold mornings.

If you miss breakfast at home, there are ample opportunities to eat on the street, where vendors sell everything from eggs to bbq.

Or you can stop for some "coffee language." Few Chinese are fluent.

Our bicycles were purchased in September from one of the many local bike shops. They are not the famous Giant® brand recognized here as the Cadillac of bikes (we went cheaper) and after a mere 8 months, like many of the things we’ve purchased here, they are beginning to fall apart. On my bike, the front derailleur no longer works and both plastic gear shift levers, weakened by sun exposure, have snapped off, one at the expense of my right thumbnail, to be replaced (25 yuan) with sturdier versions. My unbelievably heavy ride resembles a mountain bike only in appearance, and its model name—the Wangpai Beartrap—advertised by a decal on the blue and silver frame, attempts to make up for other shortcomings (I did not buy the fancier Wangpai Big Mac). Perhaps in an unlikely encounter with an even more unlikely bear (we’ve seen almost no wild animals in China except at the meat market), the bike could be hoisted and heaved, it’s formidable weight slowing the bruin long enough for escape.

I strap my book bag onto the bike rack, plug myself into my IPOD, and get ready to ride.

An IPOD can go a long way towards easing the transition to another culture and at times, obliterating it. I joined the IPOD generation before we left for China, when I purchased our 20 Gb model at the UW Bookstore and then downloaded all of the songs we liked (including a substantial collection of songs for 4-year-olds) from our not-so-extensive CD collection onto it in the weeks prior to our departure. Total space occupied by all of the music I could cull from 50 or more CDs: 1 Gb. I use the remaining 19 Gb for photo downloads when traveling, but mostly I just enjoy being able to plug into music now and then to escape the relentless low-fidelity megaphone-broadcast Chinese pop that assaults you on the streets of Lijiang where stores blast bad music presumably to attract the attention of Chinese consumers (and to repel Western ones??!!).

Chinese friends in Zhongdian last winter listening to bad Chinese pop on their shared MP3. I use our IPOD to block out this kind of music.

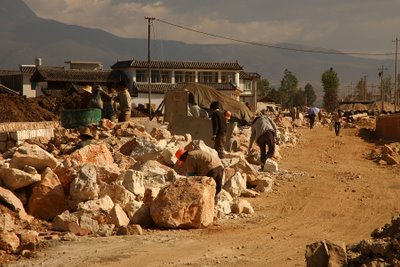

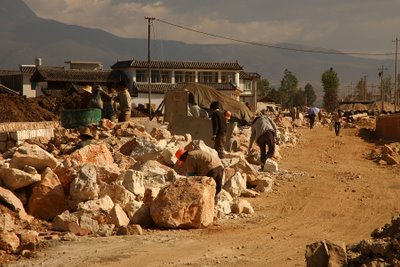

Having an IPOD can create some strange juxtapositions. One morning I turned on Lenny Kravitz’ version of American Woman just in time to round a corner in our neighborhood where a beautiful little Naxi girl clutching a white lily was riding up the stone street on her aging grandfather’s back. Another time I mellowed out to Louis Armstrong singing What a Wonderful World It Would Be as a man peddled past on a 3-wheel bicycle cart full of dead pigs, heading towards the market. Sometimes the sound track is more appropriate. Bruce Cockburn’s version of the Monty Python classic, Always Look on the Bright Side of Life (from “The Life of Brian”) makes sense as day after day you ride past men in the hot sun whose job is to hand chisel boulders into building blocks for a few dollars a day. And every day as I ride past they find the energy and spirit to wave, smile and say “hello” to the passing foreigner.

Some things in life are bad

They can really make you mad

Other things just make you swear and curse.

When you're chewing on life's gristle

Don't grumble, give a whistle

And this'll help things turn out for the best...

Men breaking rocks. Some things in life are bad.

The steepest part of the ride to work is short and over quickly—up the stone-paved street in our neighborhood, past two small stores that sell everything from baijiu and cigarettes to milk and medicine and then past several abandoned mud buildings where the smell of sewage is noticeable.

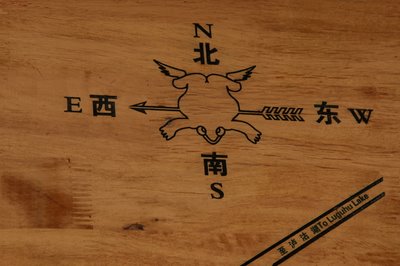

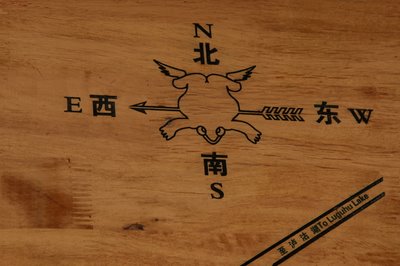

If you get confused about directions as you ride, there are some helpful signs posted to orient the tourists in town.

I turn onto JinHong Lu—the asphalt road connecting our neighborhood in the farthest east part of Old Town to the bustle of New Town. A short and gentle incline on JinHong brings me to the top of the hill and I coast down the other side, helmetless along with all the Chinese riders (short of a full-blown motorcycle helmet, there is nothing to be bought here), weaving among taxis, buses and other cyclists, and passing little storage-unit sized stores selling everything from plastic pipe to live chickens. On the sidewalks, people wash their hair, catch up on the morning gossip, or walk their kids to school. On the street, vendors haul bike carts laden with the perforated charcoal cylinders used for cooking, their bikes too heavy to pedal.

The view down the hill on Jinhong Lu.

A typical 3 wheeled bike cart--used here to haul everything from charcoal to dumpling steamers (with the dumplings being cooked en route) to spouses or children.

Veering north onto Xin Da Jie, one of the main north-south avenues through town, I pedal past more shops, more people and more megaphones – the latter blasting Chinese pop so loudly that my IPOD can’t drown it out. Embarrassingly, I now recognize most of the bad Chinese songs, and secretly hum some of them when I’m not paying attention, in the same way one might hypothetically find oneself humming “Brandy, your a fine girl...” and then stop in horror.

The intersection of JinHong and Xin Da. Avoid those swerving taxis.

The view north up Xin Da Jie.

Chairman Mao watches peacefully over Xin Da Jie. The official line is that Mao was 70% good and 30% bad but he is still visible in 100% of the substantial towns in China.

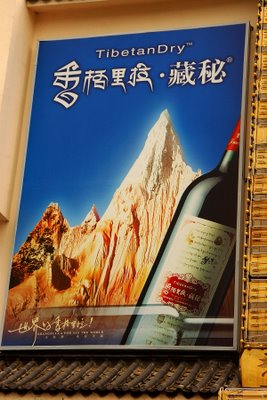

Advertising is entertaining in itself. What IS that peak?

Soon though, I bear left, crossing traffic to enter a quieter street lined with new buildings, almost all unoccupied. I read that Ernst and Young (a U.S. accounting firm) recently withdrew their estimate that Chinese banks may be sitting on over $900 billion in bad loans—many for unviable construction projects. The company cited a lack of firm evidence for this estimate though from my perspective here in Lijiang, where they build wildly on almost every city block, and where many of the new buildings remain unoccupied, one has to wonder if the estimate is low rather than high. In Old Town, a successful restaurant recently opened a new outlet in a building that reportedly cost them over $100,000 USD to rent and several hundred thousand more to renovate. You have to sell a lot of rice and stir fry to recoup that kind of investment, no matter how popular your restaurant is.

A typically brand new and unoccupied building in Lijiang. Who paid for this? The Bank of China?

On my left, pasted across the entire width of the second floor of a modern building, a giant poster of a Medieval Amazon Dominatrix looms large, cleavage taunting and exaggerated eyebrows threatening a woman on her way to empty her mopping bucket into the alley. I round a traffic circle, alert to the many opportunities for car/bus/truck/bike collisions and pedal at last onto the small road that leads the last few kilometers to the college.

A warrior princess watches over Lijiang.

At last I turn onto the poorly maintained road leading directly from town to the college, and ride past a scrappy mix of traditional Naxi houses, small fruit orchards, ugly modern buildings and semi-industrial sweatshops where people manufacture cinderblocks, furniture and charcoal or amass dangerous piles of scrap material in all its sharp, raw, recyclable glory. Masters of simile and metaphor, we chose our words carefully when we renamed this road “the bumpy way” for its substantial potholes and cobbled stretches. It has become substantially more bumpy in the last several months since becoming a construction zone. The road is being widened—from a narrow two lane to a 4-lane divided highway that will offer tour buses a direct route from town to Jade Dragon Snow Mountain.

A view of construction on "the bumpy way."

Public bus number 3 bounces along through construction.

Though the road itself is a mess, farms and orchards line the route. In the spring, the fruit trees provided a nice break from dust and a great fragrance too.

An orchard along the route.

With the construction comes commuting inconveniences, like backhoes ripping trees out of the ground and suspending them from steel cables overhead as you cower, or dump trucks piled too high with boulders teetering through the potholes or Ellen’s favorite, thick choking dust, but it also brings a chance to see the Chinese economy in action. Workers swarm over the 3 kilometer long site, and the project progresses quickly by virtue of sheer labor. In the 2 months or so since the project began, workers have—by hand—built substantial stone walls on both sides of the new highway corner with stones shaped using hammer and chisel by men pecking away at them for 8 or more hours a day. The stones are held together with mortar, every bucketful of which has been mixed by hand and carried to the stone masons. The potential for productivity gains are mind boggling, as is the potential for unemployment.

More rock breakers pecking away at huge piles of boulders with a hammer and a small collection of chisels.

Stone walls like this one, that extends for miles, are the fruits of the rock breakers' labor. Each stone has been hand chiseled from big irregular boulders.

And then the commute is over – I emerge back onto pavement, stop at the little store by the college to buy a yogurt or a bag of bbq potato chips, pedal past students cowering from the sun beneath their umbrellas (they don’t want their skin to “turn black” and they certainly don’t want to look like people who do manual labor in the sun. They are the new emerging middle class). Finally, I ride through the school gate and wrestle with that pre-teaching pit in my stomach that comes from gathering the energy necessary to try to generate enthusiasm for learning English.

At 8:00 a.m., class begins.

Get those umbrellas out--the sun is shining.

Students ready for a 2-hour class.

Ellen's preferred route follows Shangrila Street from town out to the school. The views are not too bad and the road is not devoid of cultural interest either.

"Stick" tree plantings along the Shangrila route to school. Ellen is flabbergasted that these miserable sticks, stuffed into the ground and given minimal water, eventually thrive and become trees. But it's true.

Our commute doesn't leave us looking quite a clean and perky as this shampoo model on a billboard in Lijiang.

To put this into perspective I should say that we’re already beginning to grieve (not too strong a word) our late July departure from this extraordinary place. It isn’t just the trips we’ve taken that we’ll miss. It’s also daily life; the glimpses of things simultaneously insignificant and remarkable. These glimpses will be remembered as fondly as sunrises on big mountains or shadows settling along the Yangze. The 30-minute bicycle commute each day is part of our mental landscape and on almost every ride, I see something that I want to remember.

Images like this are part of every day and every trip out of the house.

A typical teaching day for us begins at about 6:00 a.m. when we open our eyes and, from under the heavy comforter on our cobbled-together but comfortable bed (foam mattresses atop roughcut boards resting precariously on stacks of bricks constrained within a dilapidated frame), have a look through open louver doors into the courtyard, still in shadow, and to the sky, just growing light. If we sleep a little late the sun wakes us up, reflecting off the chrome tank that feeds the solar hot water heater which on a sunny day will produce plenty of water for dribbling gravity-fed showers. But we don’t worry as much about hygiene here as we do in the States, and showers can usually wait for hot afternoons, when the breeze that filters through the mostly open cinder-block bathroom doesn’t seem so daunting.

The courtyard of our house in Old Town. The pebble surface makes for wobbly trips to the bathroom in the middle of the night but it is a nice place to wake up in the morning.

Our solar hot water heater. "China's best brand" according to the decal.

Living in a courtyard house is a little like camping out. There is no heat unless you huddle around an electric space heater, light a charcoal fire in a brazier or leave the kitchen gas burners on a little longer than necessary after boiling water for coffee. But it’s almost summer now and mornings are warm—so the barefoot hobble across the pebble-paved courtyard to the bathroom is not so bad. And at night, from our bed, we can see the stars.

I get up and get dressed, putting on one of my two “nice” teaching shirts and a pair of Levi’s—all now threadbare after 8 months, but still more appropriate than showing up to teach in a t-shirt. When we leave China the shirts will be left behind, along with much of the flotsam we inveterate American consumers have accumulated here—pots and pans, pressure cooker, DVD player, stacks of pirated DVDs, English novels, day packs, bikes and our now rarely used electric space heater.

In the kitchen, I brew a cup of Yunnan coffee—spooned into my coffee filter from a plastic ice cream container that once every couple of weeks I get refilled at a local cafe for 40 yuan (about $5). The coffee isn’t bad, and it’s a lot better when I have real cream than when condensed milk is my only option. The cream comes from Kunming (10 hours away) via another cafe (The Prague) that orders it for us, and it’s a luxury that improves my morning immeasurably.

Bei in the kitchen. We have a two burner gas stove which doubles as a heat source on cold mornings.

If you miss breakfast at home, there are ample opportunities to eat on the street, where vendors sell everything from eggs to bbq.

Or you can stop for some "coffee language." Few Chinese are fluent.

Our bicycles were purchased in September from one of the many local bike shops. They are not the famous Giant® brand recognized here as the Cadillac of bikes (we went cheaper) and after a mere 8 months, like many of the things we’ve purchased here, they are beginning to fall apart. On my bike, the front derailleur no longer works and both plastic gear shift levers, weakened by sun exposure, have snapped off, one at the expense of my right thumbnail, to be replaced (25 yuan) with sturdier versions. My unbelievably heavy ride resembles a mountain bike only in appearance, and its model name—the Wangpai Beartrap—advertised by a decal on the blue and silver frame, attempts to make up for other shortcomings (I did not buy the fancier Wangpai Big Mac). Perhaps in an unlikely encounter with an even more unlikely bear (we’ve seen almost no wild animals in China except at the meat market), the bike could be hoisted and heaved, it’s formidable weight slowing the bruin long enough for escape.

I strap my book bag onto the bike rack, plug myself into my IPOD, and get ready to ride.

An IPOD can go a long way towards easing the transition to another culture and at times, obliterating it. I joined the IPOD generation before we left for China, when I purchased our 20 Gb model at the UW Bookstore and then downloaded all of the songs we liked (including a substantial collection of songs for 4-year-olds) from our not-so-extensive CD collection onto it in the weeks prior to our departure. Total space occupied by all of the music I could cull from 50 or more CDs: 1 Gb. I use the remaining 19 Gb for photo downloads when traveling, but mostly I just enjoy being able to plug into music now and then to escape the relentless low-fidelity megaphone-broadcast Chinese pop that assaults you on the streets of Lijiang where stores blast bad music presumably to attract the attention of Chinese consumers (and to repel Western ones??!!).

Chinese friends in Zhongdian last winter listening to bad Chinese pop on their shared MP3. I use our IPOD to block out this kind of music.

Having an IPOD can create some strange juxtapositions. One morning I turned on Lenny Kravitz’ version of American Woman just in time to round a corner in our neighborhood where a beautiful little Naxi girl clutching a white lily was riding up the stone street on her aging grandfather’s back. Another time I mellowed out to Louis Armstrong singing What a Wonderful World It Would Be as a man peddled past on a 3-wheel bicycle cart full of dead pigs, heading towards the market. Sometimes the sound track is more appropriate. Bruce Cockburn’s version of the Monty Python classic, Always Look on the Bright Side of Life (from “The Life of Brian”) makes sense as day after day you ride past men in the hot sun whose job is to hand chisel boulders into building blocks for a few dollars a day. And every day as I ride past they find the energy and spirit to wave, smile and say “hello” to the passing foreigner.

Some things in life are bad

They can really make you mad

Other things just make you swear and curse.

When you're chewing on life's gristle

Don't grumble, give a whistle

And this'll help things turn out for the best...

Men breaking rocks. Some things in life are bad.

The steepest part of the ride to work is short and over quickly—up the stone-paved street in our neighborhood, past two small stores that sell everything from baijiu and cigarettes to milk and medicine and then past several abandoned mud buildings where the smell of sewage is noticeable.

If you get confused about directions as you ride, there are some helpful signs posted to orient the tourists in town.

I turn onto JinHong Lu—the asphalt road connecting our neighborhood in the farthest east part of Old Town to the bustle of New Town. A short and gentle incline on JinHong brings me to the top of the hill and I coast down the other side, helmetless along with all the Chinese riders (short of a full-blown motorcycle helmet, there is nothing to be bought here), weaving among taxis, buses and other cyclists, and passing little storage-unit sized stores selling everything from plastic pipe to live chickens. On the sidewalks, people wash their hair, catch up on the morning gossip, or walk their kids to school. On the street, vendors haul bike carts laden with the perforated charcoal cylinders used for cooking, their bikes too heavy to pedal.

The view down the hill on Jinhong Lu.

A typical 3 wheeled bike cart--used here to haul everything from charcoal to dumpling steamers (with the dumplings being cooked en route) to spouses or children.

Veering north onto Xin Da Jie, one of the main north-south avenues through town, I pedal past more shops, more people and more megaphones – the latter blasting Chinese pop so loudly that my IPOD can’t drown it out. Embarrassingly, I now recognize most of the bad Chinese songs, and secretly hum some of them when I’m not paying attention, in the same way one might hypothetically find oneself humming “Brandy, your a fine girl...” and then stop in horror.

The intersection of JinHong and Xin Da. Avoid those swerving taxis.

The view north up Xin Da Jie.

Chairman Mao watches peacefully over Xin Da Jie. The official line is that Mao was 70% good and 30% bad but he is still visible in 100% of the substantial towns in China.

Advertising is entertaining in itself. What IS that peak?

Soon though, I bear left, crossing traffic to enter a quieter street lined with new buildings, almost all unoccupied. I read that Ernst and Young (a U.S. accounting firm) recently withdrew their estimate that Chinese banks may be sitting on over $900 billion in bad loans—many for unviable construction projects. The company cited a lack of firm evidence for this estimate though from my perspective here in Lijiang, where they build wildly on almost every city block, and where many of the new buildings remain unoccupied, one has to wonder if the estimate is low rather than high. In Old Town, a successful restaurant recently opened a new outlet in a building that reportedly cost them over $100,000 USD to rent and several hundred thousand more to renovate. You have to sell a lot of rice and stir fry to recoup that kind of investment, no matter how popular your restaurant is.

A typically brand new and unoccupied building in Lijiang. Who paid for this? The Bank of China?

On my left, pasted across the entire width of the second floor of a modern building, a giant poster of a Medieval Amazon Dominatrix looms large, cleavage taunting and exaggerated eyebrows threatening a woman on her way to empty her mopping bucket into the alley. I round a traffic circle, alert to the many opportunities for car/bus/truck/bike collisions and pedal at last onto the small road that leads the last few kilometers to the college.

A warrior princess watches over Lijiang.

At last I turn onto the poorly maintained road leading directly from town to the college, and ride past a scrappy mix of traditional Naxi houses, small fruit orchards, ugly modern buildings and semi-industrial sweatshops where people manufacture cinderblocks, furniture and charcoal or amass dangerous piles of scrap material in all its sharp, raw, recyclable glory. Masters of simile and metaphor, we chose our words carefully when we renamed this road “the bumpy way” for its substantial potholes and cobbled stretches. It has become substantially more bumpy in the last several months since becoming a construction zone. The road is being widened—from a narrow two lane to a 4-lane divided highway that will offer tour buses a direct route from town to Jade Dragon Snow Mountain.

A view of construction on "the bumpy way."

Public bus number 3 bounces along through construction.

Though the road itself is a mess, farms and orchards line the route. In the spring, the fruit trees provided a nice break from dust and a great fragrance too.

An orchard along the route.

With the construction comes commuting inconveniences, like backhoes ripping trees out of the ground and suspending them from steel cables overhead as you cower, or dump trucks piled too high with boulders teetering through the potholes or Ellen’s favorite, thick choking dust, but it also brings a chance to see the Chinese economy in action. Workers swarm over the 3 kilometer long site, and the project progresses quickly by virtue of sheer labor. In the 2 months or so since the project began, workers have—by hand—built substantial stone walls on both sides of the new highway corner with stones shaped using hammer and chisel by men pecking away at them for 8 or more hours a day. The stones are held together with mortar, every bucketful of which has been mixed by hand and carried to the stone masons. The potential for productivity gains are mind boggling, as is the potential for unemployment.

More rock breakers pecking away at huge piles of boulders with a hammer and a small collection of chisels.

Stone walls like this one, that extends for miles, are the fruits of the rock breakers' labor. Each stone has been hand chiseled from big irregular boulders.

And then the commute is over – I emerge back onto pavement, stop at the little store by the college to buy a yogurt or a bag of bbq potato chips, pedal past students cowering from the sun beneath their umbrellas (they don’t want their skin to “turn black” and they certainly don’t want to look like people who do manual labor in the sun. They are the new emerging middle class). Finally, I ride through the school gate and wrestle with that pre-teaching pit in my stomach that comes from gathering the energy necessary to try to generate enthusiasm for learning English.

At 8:00 a.m., class begins.

Get those umbrellas out--the sun is shining.

Students ready for a 2-hour class.

2 Comments:

I though your student are children. I was amazed when i see them here. They are old. Can you consider this as high school or college. Is this setting a small town or a city.

By the way, i hope you could give me a link to my blog http://depedteacher.blogspot.com

Lance--we taught college students at a small college in Lijiang, which is a small town in Yunnan.

Post a Comment

<< Home