Yubeng 2 -- The Tourism Dilemma

First, let me say that things are getting a little busy around here with our impending departure. We finish teaching on June 23 and then will travel until the 19th of July when we fly to the U.S. We’re in the midst of finishing a semester, packing the formidable pile of stuff that we’ve accumulated, shipping things back to ourselves, trying to plan a lot of in and out of China travel and saying goodbyes to friends and students. All to say that blog entries are going to be sparse for a while. I’ll continue blogging here in China and after we return to the U.S. until I have worked through a long list of topics that I’d like to discuss (not the least of which is our planned orphanage visits). But it may take a while. For now, I’ll relate a trip back north to the Meili Snow Mountains and Yubeng that we did over the May holiday (WuYi).

Visiting a tiny, traditional Tibetan village huddled at the base of enormous glaciated peaks on the Yunnan frontier is a once in a lifetime experience worth repeating. And since Bei and Ellen hadn’t had the chance, we returned to Yubeng over the May 1 (WuYi) holiday, along with hordes of Chinese tourists, also eager to experience “nature” and “Tibet.”

Yubeng is beautiful and increased tourism is inevitable.

Tourists get their first glimpse of the Yubeng valley from this pass, where they can also buy bottled drinks and other trash-producing snacks.

Traditional villages anywhere in the world offer tourists the ever more unusual opportunity to glimpse ways of life quickly being consumed by roads, cell phones and the relentless onslaught of the growing global economy. We Westerners are especially drawn to places that are “untouched.” But the very act of observing changes the thing being observed in profound ways (just ask Heisenberg. Our return to Yubeng was a great chance to see a still-beautiful and largely traditional Tibetan-style village, but it was also tainted by the realization that the huge mobs of tourists (that we were a part of) who descend on this tiny place are rapidly changing the very thing they come so far to see.

Young boys ride a horse through Yubeng. What will life be like for them 10 years from now? And what will their children's lives be like?

Tourists crossing the pass into Yubeng.

An editorial published on May 12 in The New York Times described a tribe (the Nukak) from the jungles of Colombia that recently renounced their traditional ways to move from ancestral lands into a more modern village. The Times commented:

“We have no clearer idea what it would mean to live a subsistence life in the Colombian jungle than the Nukak have of living even on the fringes of the modern world. In one sense, there has never been a better time for a people like the Nukak to leave the wild. They'll find medical care, sustenance and a genuine attempt at cultural respect that would have been impossible years ago. Yet the fact that they're leaving suggests how much their world — and ours — has been impaired.

The Nukak have every right to make this decision for themselves. But it's hard to escape the feeling that their self-sustaining existence — which went almost entirely unnoticed by the rest of the world — was holding something open for us, something that has now been lost.”

Yubeng, of course, is not a tribal village in the Colombian jungle, but some of the issues are analogous. The village is small – it had 133 residents in 2001 and I doubt that the population has changed substantially in 5 years. Yubeng is isolated—there is no road access and the foot-trail to the village climbs steeply over a mountain pass that can be blocked by snow in the winter. The people of Yubeng, though not isolated from the outside world, still live a simple life—cutting timber, raising yaks and other animals and farming on the small areas flat enough to be plowed. And life has been hard here. Health care is difficult to access and other services are nonexistent. In a 2001 New York Times piece by Erik Eckholm, the author says:

"But if this is almost paradise, that "almost" contains a world of sorrows the people of Yubeng could do without.

Mr. Aqianbu [a Yubeng resident and guest house owner] matter-of-factly gave an example. He, his younger brother and the wife they share, in the polyandrous triangle common to the region, have watched three of their four babies die -- a result of the near-total lack of modern medicine, the poor sanitation and nutrition and, ultimately, the poverty and isolation of a village that is an arduous six-hour hike from the nearest dirt road.

They are proud of their surviving daughter, but they are not happy that to attend school beyond the third grade she must make that same hike over a high mountain pass, then stay at school for two weeks at a time, paying dormitory fees that are a terrible strain."

A woman carries a load from the Yubeng fields back to her house. Farming is hard work and the lure of a tourist economy is strong.

Our friends Scott Lehman and Bay Roberts visited Yubeng several years ago before it became so visible on the tourism circuit and Scott constructed the first outhouse (suitable for “western wide rides” according to Scott) in the village. Outhouses, along with visitors, now abound though they are often poorly constructed, thoughtlessly located, and overused so that raw sewage finds its way into the streams that run through the valley on their way to the Mekong several miles downstream.

Our guesthouse in Yubeng. One of many that are being built to accomodate increased numbers of tourists.

When I visited Yubeng alone in February, there were a few Chinese tourists in town and guesthouses were quiet. One could imagine the village as it has been for hundreds of years and could, with little effort, explore the area with only yaks and pigs for company.

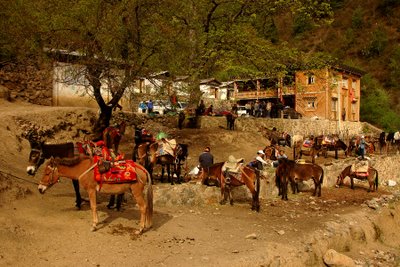

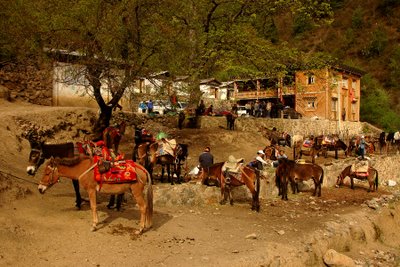

But the May 1 holiday in China is like Spring Break for the entire country, and the scene at Yubeng had utterly changed. We hiked from the trailhead accompanied by an almost continuous stream of Chinese tourists (over 200 per day over the holidays, we were told), most on horses led by hard-working locals who sometimes make two trips a day over the pass to maximize their salaries (horse + horse packer costs 160 yuan per trip, which is about $20, a sizeable sum in rural China). Not only do the horsepackers rush up and down the mountain pulling often reluctant horses and mules, but they often do so while carrying the substantial backpacks of their clients. They are so fit that it is an endurance workout to try to keep up with them (Bei rode a horse, so we ran along behind).

The trailhead for the trip to Yubeng. The once sleepy place is a mob of tourists and horses, waiting to join forces for the trip over the pass.

For many Chinese, outdoor recreation is a new pastime—the emerging middle class I suppose – and they struggle with great determination to reach places like Yubeng. Those on horses often seem to be doing all in their power to insulate themselves from the “nature” that they came to see. Riding in the hot sun, they dress in full gortex suits, boots, gators and substantial sun hats. We passed one group of older tourists who added to this outfit a complete facial wrap of thin gauzy material and large sunglasses to prevent sun from touching any skin, so that they resembled Saharan Touregs riding camels across blistering dunes.

The disconnect between man and the environment among many Chinese manifests itself in an oblivious disregard for the effects of so many people. Trash is a big problem and the area along the trail, which climbs through fir forest and blossoming rhododendron stands, was littered with plastic bottles, food wrappers, toilet paper and other refuse. Above snowline while on a dayhike, I saw tree-wells where trash accumulated on melting snow. In the village itself, workers cleaning rooms tossed refuse off of balconies onto steep hillsides to contribute to terracing efforts in front of the buildings (making ever larger viewing platforms for tourists atop the trash). A picturesque stupa in the upper village sits beside a plastic bottle dump, where thousands of drinking water containers are sequestered in a small fenced area to slowly decompose in the sun.

This area near a stupa, though beautiful, is also right beside a large dump where plastic bottles and other refuse are tossed into a small, fenced area.

And the flow of people like ourselves also brings change by virtue of the money we pour into the local economy. If you were a villager, would you preserve subsistence farming and a “quaint” lifestyle or would you engage with the lucrative tourist trade?

There is much construction in Yubeng these days and many families have upgraded their traditional Tibetan courtyard homes into tourist guest houses (still rustic). And who can blame them? In 2001 Eckholm wrote that:

"Now the people of the region, especially in more pristine places like Yubeng, are facing a challenge that many other parts of China have already failed: finding a way to prosper, while preserving their unique environment.

To solve this problem, the people of Yubeng are engaged in an unusual dialogue about their future -- part of a collaboration between the Yunnan government and the United States-based Nature Conservancy, one of the largest private international conservation groups.

"The goal of the Nature Conservancy is to protect biodiversity," said Rose Niu, a 39-year-old member of Yunnan's Naxi minority group who has a master's degree in resource management and directs the conservancy's China project.

"But here, it's very clear that you can't protect nature unless you work together with local communities and preserve the culture too," she said. "We especially need to promote the traditions calling for harmony with nature.""

Houses in this area are built of rammed earth and huge timbers culled from rare mature forest. Though logging was outlawed in 1998, villages still have rights to use forest resources.

There are big trees around Yubeng--a rarity in our experience in Yunnan. But many of these trees are used for the enormous posts that are part of traditional architecture in this area.

A water powered sawmill for cutting logs into boards. This mill near Yubeng appeared to be abandoned.

Boards stacked to dry near Yubeng. I believe that these are milled using chainsaws or other gas powered tools, though I'm not certain.

After our trip to Yubeng in May, I’d have to conclude that at least in some important ways, the challenges expressed so hopefully by Ms. Niu are not being met. What Yubeng needs is a sustainable way to support the inevitable increase in tourism that has already been unleashed on an area too beautiful to remain secret, while giving the people there a chance to prosper without destroying the very thing tourists come to see.

At the end of his article, Eckholm quoted a man named Amu, one of two village chiefs when the article was written in 2001:

“Of course, all of us are looking forward to a better life," he [Amu] said. "We need a road most of all, and we need a bigger hydropower station to give us steady electricity for cooking."

“We see tourism as our best hope," Mr. Amu said. "We welcome more tourists here, but those that bring destruction will not be allowed.”

And although if I lived in a village where my daughter’s life was in danger because of the lack of accessible medical care, I too would wish for a road, I also have to hope for and wonder if there are other solutions – regular visits to the village by doctors, establishment of a clinic supported by tourism and conservation dollars or other creative programs. For is not just tourists who “bring destruction” to pristine places in China.

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) is one organization that recognizes the huge opportunities that we have in China to preserve both culture and an unequaled environmental resource. I have to hope that groups like this have the capability of making a big difference. TNC states on one of their web pages that:

"To meet the conservation needs of this area and its people, the Conservancy has completed a draft resource management plan for Meili Snow Mountain that places special emphasis on reducing the threats of future mass tourism projects. Moreover, the Conservancy will continue to work closely with Tibetan communities, government officials, and technical experts to implement the plan."

To be successful in places like Yubeng, these plans require an influx of money from outside (and inside) China and letters expressing the hope that solutions can be found that address the very real problems faced by local people while at the same time preserving what is left of this place and culture.

If any of you are interested, TNC has an excellent web site for their China program:

The Nature Conservancy China Program

And it is not too late. The Meili Mountains are still beautiful, the Yubeng valley is still spectacular and the people who live there still lead a simple life tied largely to the land. On our last day in Yubeng before joining the hordes for the hike out to “civilization” Ellen and I took turns walking through the upper village to a stream where the rhododendrons were particularly spectacular. On her way back through the village, Ellen was startled by villagers announcing excitedly to one another: “Feiji! Feiji!”

As one they turned their heads upwards to watch a single passenger jet pierce the Tibetan sky.

Ellen and Bei on their way to our ride to Deqin walk through "Old Town" Zhongdian. Much of old town has been constructed recently for tourists and much is still under construction.

Bei dances with the locals in Zhongdian. We were told that the dancing was original forced by the government to promote tourism but has since taken on a life of its own among both tourists and locals.

Things for sale in a Zhongdian market frequented by locals and tourists.

One of several "first bends" of the Yangze River. This is a standard stop for tourists on their way north from Zhongdian.

Bei and Ellen visiting with monks at a monastery near the town of Benzilan north of Zhongdian. Bei and the monks were mutually fascinated.

Bei and I in Xidang above the Mekong River.

A detail from a stupa in Xidang near the Yubeng trailhead.

Crumbling tower in Xidang.

Prayer flags on a ridge above Xidang.

Herders move along a dirt road above Xidang. The steep terrain in the background is typical of the country along the Mekong and access to the area is difficult as a result.

Bei leaving Yubeng.

A string of horses and mules carrying tourists and gear into Yubeng for the holiday.

The Meili Snow Mountains. Not only is the village itself beautiful, but it rests just below peaks like this. How can tourists not come here?

Rhododendrons in bloom near Yubeng.

The afternoon view across the fields and forests near upper Yubeng.

A bench near the upper village of Yubeng. Afternoon light highlights the trees that were flush with new leaves when we were there in early May.

Bei with a couple of the women that are part of the family that owns the guesthouse where we stayed.

Ellen in the dining room at the Yubeng guesthouse where we stayed. When I took this photo she was unaware of the backdrop lurking behind her.

Tourists and their baggage catch a ride through upper Yubeng in the back of a tractor.

Rhododendrons near Yubeng. Yunnan is famous for them and they bloom all summer long.

A view from the fields near the upper village of Yubeng.

Locals watching the steady stream of tourists pouring into the village below.

Bei preparing to leave Yubeng on her trusty steed.

Bei and Ellen on the pass above Yubeng on our way out.

Visiting a tiny, traditional Tibetan village huddled at the base of enormous glaciated peaks on the Yunnan frontier is a once in a lifetime experience worth repeating. And since Bei and Ellen hadn’t had the chance, we returned to Yubeng over the May 1 (WuYi) holiday, along with hordes of Chinese tourists, also eager to experience “nature” and “Tibet.”

Yubeng is beautiful and increased tourism is inevitable.

Tourists get their first glimpse of the Yubeng valley from this pass, where they can also buy bottled drinks and other trash-producing snacks.

Traditional villages anywhere in the world offer tourists the ever more unusual opportunity to glimpse ways of life quickly being consumed by roads, cell phones and the relentless onslaught of the growing global economy. We Westerners are especially drawn to places that are “untouched.” But the very act of observing changes the thing being observed in profound ways (just ask Heisenberg. Our return to Yubeng was a great chance to see a still-beautiful and largely traditional Tibetan-style village, but it was also tainted by the realization that the huge mobs of tourists (that we were a part of) who descend on this tiny place are rapidly changing the very thing they come so far to see.

Young boys ride a horse through Yubeng. What will life be like for them 10 years from now? And what will their children's lives be like?

Tourists crossing the pass into Yubeng.

An editorial published on May 12 in The New York Times described a tribe (the Nukak) from the jungles of Colombia that recently renounced their traditional ways to move from ancestral lands into a more modern village. The Times commented:

“We have no clearer idea what it would mean to live a subsistence life in the Colombian jungle than the Nukak have of living even on the fringes of the modern world. In one sense, there has never been a better time for a people like the Nukak to leave the wild. They'll find medical care, sustenance and a genuine attempt at cultural respect that would have been impossible years ago. Yet the fact that they're leaving suggests how much their world — and ours — has been impaired.

The Nukak have every right to make this decision for themselves. But it's hard to escape the feeling that their self-sustaining existence — which went almost entirely unnoticed by the rest of the world — was holding something open for us, something that has now been lost.”

Yubeng, of course, is not a tribal village in the Colombian jungle, but some of the issues are analogous. The village is small – it had 133 residents in 2001 and I doubt that the population has changed substantially in 5 years. Yubeng is isolated—there is no road access and the foot-trail to the village climbs steeply over a mountain pass that can be blocked by snow in the winter. The people of Yubeng, though not isolated from the outside world, still live a simple life—cutting timber, raising yaks and other animals and farming on the small areas flat enough to be plowed. And life has been hard here. Health care is difficult to access and other services are nonexistent. In a 2001 New York Times piece by Erik Eckholm, the author says:

"But if this is almost paradise, that "almost" contains a world of sorrows the people of Yubeng could do without.

Mr. Aqianbu [a Yubeng resident and guest house owner] matter-of-factly gave an example. He, his younger brother and the wife they share, in the polyandrous triangle common to the region, have watched three of their four babies die -- a result of the near-total lack of modern medicine, the poor sanitation and nutrition and, ultimately, the poverty and isolation of a village that is an arduous six-hour hike from the nearest dirt road.

They are proud of their surviving daughter, but they are not happy that to attend school beyond the third grade she must make that same hike over a high mountain pass, then stay at school for two weeks at a time, paying dormitory fees that are a terrible strain."

A woman carries a load from the Yubeng fields back to her house. Farming is hard work and the lure of a tourist economy is strong.

Our friends Scott Lehman and Bay Roberts visited Yubeng several years ago before it became so visible on the tourism circuit and Scott constructed the first outhouse (suitable for “western wide rides” according to Scott) in the village. Outhouses, along with visitors, now abound though they are often poorly constructed, thoughtlessly located, and overused so that raw sewage finds its way into the streams that run through the valley on their way to the Mekong several miles downstream.

Our guesthouse in Yubeng. One of many that are being built to accomodate increased numbers of tourists.

When I visited Yubeng alone in February, there were a few Chinese tourists in town and guesthouses were quiet. One could imagine the village as it has been for hundreds of years and could, with little effort, explore the area with only yaks and pigs for company.

But the May 1 holiday in China is like Spring Break for the entire country, and the scene at Yubeng had utterly changed. We hiked from the trailhead accompanied by an almost continuous stream of Chinese tourists (over 200 per day over the holidays, we were told), most on horses led by hard-working locals who sometimes make two trips a day over the pass to maximize their salaries (horse + horse packer costs 160 yuan per trip, which is about $20, a sizeable sum in rural China). Not only do the horsepackers rush up and down the mountain pulling often reluctant horses and mules, but they often do so while carrying the substantial backpacks of their clients. They are so fit that it is an endurance workout to try to keep up with them (Bei rode a horse, so we ran along behind).

The trailhead for the trip to Yubeng. The once sleepy place is a mob of tourists and horses, waiting to join forces for the trip over the pass.

For many Chinese, outdoor recreation is a new pastime—the emerging middle class I suppose – and they struggle with great determination to reach places like Yubeng. Those on horses often seem to be doing all in their power to insulate themselves from the “nature” that they came to see. Riding in the hot sun, they dress in full gortex suits, boots, gators and substantial sun hats. We passed one group of older tourists who added to this outfit a complete facial wrap of thin gauzy material and large sunglasses to prevent sun from touching any skin, so that they resembled Saharan Touregs riding camels across blistering dunes.

The disconnect between man and the environment among many Chinese manifests itself in an oblivious disregard for the effects of so many people. Trash is a big problem and the area along the trail, which climbs through fir forest and blossoming rhododendron stands, was littered with plastic bottles, food wrappers, toilet paper and other refuse. Above snowline while on a dayhike, I saw tree-wells where trash accumulated on melting snow. In the village itself, workers cleaning rooms tossed refuse off of balconies onto steep hillsides to contribute to terracing efforts in front of the buildings (making ever larger viewing platforms for tourists atop the trash). A picturesque stupa in the upper village sits beside a plastic bottle dump, where thousands of drinking water containers are sequestered in a small fenced area to slowly decompose in the sun.

This area near a stupa, though beautiful, is also right beside a large dump where plastic bottles and other refuse are tossed into a small, fenced area.

And the flow of people like ourselves also brings change by virtue of the money we pour into the local economy. If you were a villager, would you preserve subsistence farming and a “quaint” lifestyle or would you engage with the lucrative tourist trade?

There is much construction in Yubeng these days and many families have upgraded their traditional Tibetan courtyard homes into tourist guest houses (still rustic). And who can blame them? In 2001 Eckholm wrote that:

"Now the people of the region, especially in more pristine places like Yubeng, are facing a challenge that many other parts of China have already failed: finding a way to prosper, while preserving their unique environment.

To solve this problem, the people of Yubeng are engaged in an unusual dialogue about their future -- part of a collaboration between the Yunnan government and the United States-based Nature Conservancy, one of the largest private international conservation groups.

"The goal of the Nature Conservancy is to protect biodiversity," said Rose Niu, a 39-year-old member of Yunnan's Naxi minority group who has a master's degree in resource management and directs the conservancy's China project.

"But here, it's very clear that you can't protect nature unless you work together with local communities and preserve the culture too," she said. "We especially need to promote the traditions calling for harmony with nature.""

Houses in this area are built of rammed earth and huge timbers culled from rare mature forest. Though logging was outlawed in 1998, villages still have rights to use forest resources.

There are big trees around Yubeng--a rarity in our experience in Yunnan. But many of these trees are used for the enormous posts that are part of traditional architecture in this area.

A water powered sawmill for cutting logs into boards. This mill near Yubeng appeared to be abandoned.

Boards stacked to dry near Yubeng. I believe that these are milled using chainsaws or other gas powered tools, though I'm not certain.

After our trip to Yubeng in May, I’d have to conclude that at least in some important ways, the challenges expressed so hopefully by Ms. Niu are not being met. What Yubeng needs is a sustainable way to support the inevitable increase in tourism that has already been unleashed on an area too beautiful to remain secret, while giving the people there a chance to prosper without destroying the very thing tourists come to see.

At the end of his article, Eckholm quoted a man named Amu, one of two village chiefs when the article was written in 2001:

“Of course, all of us are looking forward to a better life," he [Amu] said. "We need a road most of all, and we need a bigger hydropower station to give us steady electricity for cooking."

“We see tourism as our best hope," Mr. Amu said. "We welcome more tourists here, but those that bring destruction will not be allowed.”

And although if I lived in a village where my daughter’s life was in danger because of the lack of accessible medical care, I too would wish for a road, I also have to hope for and wonder if there are other solutions – regular visits to the village by doctors, establishment of a clinic supported by tourism and conservation dollars or other creative programs. For is not just tourists who “bring destruction” to pristine places in China.

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) is one organization that recognizes the huge opportunities that we have in China to preserve both culture and an unequaled environmental resource. I have to hope that groups like this have the capability of making a big difference. TNC states on one of their web pages that:

"To meet the conservation needs of this area and its people, the Conservancy has completed a draft resource management plan for Meili Snow Mountain that places special emphasis on reducing the threats of future mass tourism projects. Moreover, the Conservancy will continue to work closely with Tibetan communities, government officials, and technical experts to implement the plan."

To be successful in places like Yubeng, these plans require an influx of money from outside (and inside) China and letters expressing the hope that solutions can be found that address the very real problems faced by local people while at the same time preserving what is left of this place and culture.

If any of you are interested, TNC has an excellent web site for their China program:

The Nature Conservancy China Program

And it is not too late. The Meili Mountains are still beautiful, the Yubeng valley is still spectacular and the people who live there still lead a simple life tied largely to the land. On our last day in Yubeng before joining the hordes for the hike out to “civilization” Ellen and I took turns walking through the upper village to a stream where the rhododendrons were particularly spectacular. On her way back through the village, Ellen was startled by villagers announcing excitedly to one another: “Feiji! Feiji!”

As one they turned their heads upwards to watch a single passenger jet pierce the Tibetan sky.

Ellen and Bei on their way to our ride to Deqin walk through "Old Town" Zhongdian. Much of old town has been constructed recently for tourists and much is still under construction.

Bei dances with the locals in Zhongdian. We were told that the dancing was original forced by the government to promote tourism but has since taken on a life of its own among both tourists and locals.

Things for sale in a Zhongdian market frequented by locals and tourists.

One of several "first bends" of the Yangze River. This is a standard stop for tourists on their way north from Zhongdian.

Bei and Ellen visiting with monks at a monastery near the town of Benzilan north of Zhongdian. Bei and the monks were mutually fascinated.

Bei and I in Xidang above the Mekong River.

A detail from a stupa in Xidang near the Yubeng trailhead.

Crumbling tower in Xidang.

Prayer flags on a ridge above Xidang.

Herders move along a dirt road above Xidang. The steep terrain in the background is typical of the country along the Mekong and access to the area is difficult as a result.

Bei leaving Yubeng.

A string of horses and mules carrying tourists and gear into Yubeng for the holiday.

The Meili Snow Mountains. Not only is the village itself beautiful, but it rests just below peaks like this. How can tourists not come here?

Rhododendrons in bloom near Yubeng.

The afternoon view across the fields and forests near upper Yubeng.

A bench near the upper village of Yubeng. Afternoon light highlights the trees that were flush with new leaves when we were there in early May.

Bei with a couple of the women that are part of the family that owns the guesthouse where we stayed.

Ellen in the dining room at the Yubeng guesthouse where we stayed. When I took this photo she was unaware of the backdrop lurking behind her.

Tourists and their baggage catch a ride through upper Yubeng in the back of a tractor.

Rhododendrons near Yubeng. Yunnan is famous for them and they bloom all summer long.

A view from the fields near the upper village of Yubeng.

Locals watching the steady stream of tourists pouring into the village below.

Bei preparing to leave Yubeng on her trusty steed.

Bei and Ellen on the pass above Yubeng on our way out.

3 Comments:

Amazing blog. I could keep reading it!!! I love the pictures and the stories. One tiny thing that I noticed: Colombia and Colombian are spelled with O not U. I love your travel memories! We are going to Urumqi soon to adopt a little boy and I can't wait to experience his culture!

Thanks for the edits! I fixed those.

You might be interested in Urumqi photos that I have on flickr: http://www.flickr.com/photos/kdriese. Look in the China collection for the Urumqi set. Best of luck with your adoption! Ken

Great detail and insight in your post!

I am heading to Yubeng with friends in September. What are the guesthouses like? Do we need sleeping bags? We are trying to pack as minimally as possible.

Post a Comment

<< Home