Entering Xinjiang

Like a flash, six months have gone by and outside my window I see the snow of a Laramie winter instead of the clear blue sky of the dry season in Yunnan. Bummer! Instead of motivating to teach for two hours a day, I pack a lunch and head to my office for eight, a fact of life that I’m still not used to after our China year (will I ever be used to it again??). And instead of a half hour bike ride to work along with people toting butchered pigs and hauling baskets of vegetables, I walk to the gym at noon and ride the stationary bike while reading Newsweek. The transition has not been easy.

It gets harder to think back and remember what it was like to live in China, but this blog remains unfinished and we visited some incredible places in July 2006 – Xinjiang, Gansu, Jiangxi and finally Beijing, where we boarded a jet and emerged in the U.S. some 12 hours later to begin gaining weight. So I’ll post a few more entries to try to at least partly finish the year’s story. Probably I will mostly just add photographs from our travels with extended captions, but maybe a little commentary here and there.

We left Lijiang in late June, first giving away a small truckload of accumulated “stuff” (American consumerism is hard to shake) to a woman whose family runs a guest house in the little village of Yuhu, site of Joseph Rock’s former home at the base of Yulong Shuishan. In the pile to give away: pirated DVDs and a DVD player, mattresses, blankets, my industrial grade power converter (for charging my never-used rock climbing drill), kids books, kitchen wares, miscellaneous food, and our trusty “Beartrap” bicycles. To carry with us for the next month: a huge suitcase, a huge, heavy backpack and several smaller bags, all stuffed with things we either couldn’t mail or thought we might need. For the next month we would feel like pack animals, dragging this pile of luggage from plane to train to hotel and back again in the heat of a Chinese summer and stashing it whenever possible in “left luggage” rooms to be reclaimed after excursions. I always vow that on the NEXT trip I will travel light, but it never happens.

By the time we said goodbye to our friend Jacqueline, who rode with us to the airport, and boarded the plane to Kunming, we were too tired of packing and waiting for our last paychecks to be especially sentimental about leaving, though there were tearful goodbyes with our Naxi neighbors and Western friends and last looks towards Jade Dragon Snow Mountain.

In Kunming we boarded another plane for the long flight to Urumqi, capitol of the Xinjiang, China’s vast, westernmost province where the high mountains of the Tian Shan and the Himalaya cradle broad deserts that are the lowest and hottest places in China. The flight from Kunming took us across the edge of the Tibetan Plateau and the Qinghai Province and high empty landscapes extended off to the horizon, a temptation for future travels. The mountains just north of Qinghai lake looked especially tempting in their emptiness.

Urumqi, our initial destination, was far from empty and we deboarded into a new world from the one we had left in Yunnan. Xinjiang is dominated by the Uighur minority—Chinese Muslims—and though the Han are making a stout effort to overwhelm this population with immigration, entering Urumqi feels like leaving China for the Middle East. Men wear Muslim hats, women are often covered and minarets replace Chinese pagodas in piercing the skyline. And it isn’t just a feeling. Like Tibet, the Uyghurs have historically been more linked to Central Asia than to China, and many long for independence, much as Tibet has tried to remain separate. And uprising have been crushed by the Chinese with similar overwhelming force. Peter Hessler’s recent book “Oracle Bones” explores the Uyghur’s at least superficially and is an interesting introduction.

We spent just a couple of nights in Urumqi and a night in nearby Turfan (Turpan), an oasis in the nearby desert. Here are a few photos.

Minarets signal a major change in cultural heritage from the Naxi world of Lijiang to the Uighur Muslim world of Xinjiang and Urumqi. These two were at the "Da Bazaar" or "Big Market" in Urumqi.

The Da Bazaar was also a new world of things for sale. No more Dongba script!

Oil lamps at Da Bazaar.

All of our students who came from Xinjiang and many others who had visited here raved about the famous fruit and everywhere we went there were melons, peaches, grapes, etc. for sale on the streets.

My fascination with manequins in China was piqued by this herd.

And by this counterpart to the "pycho bride" of Shanghai. Perhaps her long lost groom?

The desert oasis of Turpan (Turfan in China) is famous for grapes and raisins. We drove through a pass in the Tian Shan to get to this place which is the Chinese equivalent of death valley--below sea level nearby and extremely hot. But grape arbors provide shade and a peaceful atmosphere.

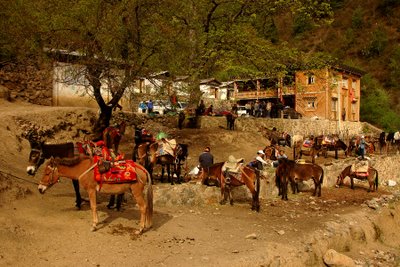

One of the common modes of transport in western China, the donkey cart.

Seman fried rice??!!

A crowd gathered in Turpan to watch a show and fireworks display.

Blue.

A thriving outdoor eating area in Turpan.

The desert outside of Turpan. Very dry and very hot, this desert gives rise to towns and vineyards by virtue of a huge network of wells and underground canals that have been dug and maintained for thousands of years.

The Flaming Mountains outside of Turpan.

Melons are everywhere. This man was carrying a few more to a vendor outside the gate of an ancient city called Gao Cheng that we were visiting.

Bei protecting herself from the hot sun at the ruins of Gao Cheng.

These kids work selling tourist stuff at the entrance to Gao Cheng. As is always the case, they were very interested in Bei.

This Uighur girl posed for us and then walked back to our van so that we could take her photo with Bei.

Bei with the Uighur girl from Gao Cheng.

We were able to get permission to visit a Uighur cemetary outside of Gao Cheng, thanks to our driver who was Uighur. This is a body carrier.

A typical Uighur (Muslim) cemetary in this area. This is the one we visited outside of Gao Cheng. The graves are expressed on the surface but often go very deep with multiple graves arranged within deep narrow pits. Wealthier families have big elaborate mausoleums, many of which were severely damaged during the Cultural Revolution. Human bones are scattered about in the dirt.

It gets harder to think back and remember what it was like to live in China, but this blog remains unfinished and we visited some incredible places in July 2006 – Xinjiang, Gansu, Jiangxi and finally Beijing, where we boarded a jet and emerged in the U.S. some 12 hours later to begin gaining weight. So I’ll post a few more entries to try to at least partly finish the year’s story. Probably I will mostly just add photographs from our travels with extended captions, but maybe a little commentary here and there.

We left Lijiang in late June, first giving away a small truckload of accumulated “stuff” (American consumerism is hard to shake) to a woman whose family runs a guest house in the little village of Yuhu, site of Joseph Rock’s former home at the base of Yulong Shuishan. In the pile to give away: pirated DVDs and a DVD player, mattresses, blankets, my industrial grade power converter (for charging my never-used rock climbing drill), kids books, kitchen wares, miscellaneous food, and our trusty “Beartrap” bicycles. To carry with us for the next month: a huge suitcase, a huge, heavy backpack and several smaller bags, all stuffed with things we either couldn’t mail or thought we might need. For the next month we would feel like pack animals, dragging this pile of luggage from plane to train to hotel and back again in the heat of a Chinese summer and stashing it whenever possible in “left luggage” rooms to be reclaimed after excursions. I always vow that on the NEXT trip I will travel light, but it never happens.

By the time we said goodbye to our friend Jacqueline, who rode with us to the airport, and boarded the plane to Kunming, we were too tired of packing and waiting for our last paychecks to be especially sentimental about leaving, though there were tearful goodbyes with our Naxi neighbors and Western friends and last looks towards Jade Dragon Snow Mountain.

In Kunming we boarded another plane for the long flight to Urumqi, capitol of the Xinjiang, China’s vast, westernmost province where the high mountains of the Tian Shan and the Himalaya cradle broad deserts that are the lowest and hottest places in China. The flight from Kunming took us across the edge of the Tibetan Plateau and the Qinghai Province and high empty landscapes extended off to the horizon, a temptation for future travels. The mountains just north of Qinghai lake looked especially tempting in their emptiness.

Urumqi, our initial destination, was far from empty and we deboarded into a new world from the one we had left in Yunnan. Xinjiang is dominated by the Uighur minority—Chinese Muslims—and though the Han are making a stout effort to overwhelm this population with immigration, entering Urumqi feels like leaving China for the Middle East. Men wear Muslim hats, women are often covered and minarets replace Chinese pagodas in piercing the skyline. And it isn’t just a feeling. Like Tibet, the Uyghurs have historically been more linked to Central Asia than to China, and many long for independence, much as Tibet has tried to remain separate. And uprising have been crushed by the Chinese with similar overwhelming force. Peter Hessler’s recent book “Oracle Bones” explores the Uyghur’s at least superficially and is an interesting introduction.

We spent just a couple of nights in Urumqi and a night in nearby Turfan (Turpan), an oasis in the nearby desert. Here are a few photos.

Minarets signal a major change in cultural heritage from the Naxi world of Lijiang to the Uighur Muslim world of Xinjiang and Urumqi. These two were at the "Da Bazaar" or "Big Market" in Urumqi.

The Da Bazaar was also a new world of things for sale. No more Dongba script!

Oil lamps at Da Bazaar.

All of our students who came from Xinjiang and many others who had visited here raved about the famous fruit and everywhere we went there were melons, peaches, grapes, etc. for sale on the streets.

My fascination with manequins in China was piqued by this herd.

And by this counterpart to the "pycho bride" of Shanghai. Perhaps her long lost groom?

The desert oasis of Turpan (Turfan in China) is famous for grapes and raisins. We drove through a pass in the Tian Shan to get to this place which is the Chinese equivalent of death valley--below sea level nearby and extremely hot. But grape arbors provide shade and a peaceful atmosphere.

One of the common modes of transport in western China, the donkey cart.

Seman fried rice??!!

A crowd gathered in Turpan to watch a show and fireworks display.

Blue.

A thriving outdoor eating area in Turpan.

The desert outside of Turpan. Very dry and very hot, this desert gives rise to towns and vineyards by virtue of a huge network of wells and underground canals that have been dug and maintained for thousands of years.

The Flaming Mountains outside of Turpan.

Melons are everywhere. This man was carrying a few more to a vendor outside the gate of an ancient city called Gao Cheng that we were visiting.

Bei protecting herself from the hot sun at the ruins of Gao Cheng.

These kids work selling tourist stuff at the entrance to Gao Cheng. As is always the case, they were very interested in Bei.

This Uighur girl posed for us and then walked back to our van so that we could take her photo with Bei.

Bei with the Uighur girl from Gao Cheng.

We were able to get permission to visit a Uighur cemetary outside of Gao Cheng, thanks to our driver who was Uighur. This is a body carrier.

A typical Uighur (Muslim) cemetary in this area. This is the one we visited outside of Gao Cheng. The graves are expressed on the surface but often go very deep with multiple graves arranged within deep narrow pits. Wealthier families have big elaborate mausoleums, many of which were severely damaged during the Cultural Revolution. Human bones are scattered about in the dirt.