Jinsha (Yangze) River Trek

The finale of our Spring Festival travels was a four day trek in mid-February along and across the Jinsha (Yangze) River in the mountains north of Lijiang. We set out with a large group: the three of us; Tony, his son Devlin and Devlin’s friend Nicole; Jacqueline and our friend Brian Collins from Seattle. The lot of us piled into a local bus in front of the college for the ride north to the beginning of the trail in a small village above the west bank of the river. From there we walked through villages occupied by four ethnic groups—Naxi, Yi, Mosuo and Pumi--in terrain that ranged from wet rhododendron forest to dry badlands, and in weather that baked us on some days and snowed on us on others. In every way it was an exceptional trip and one that is perhaps best described with photos.

Bei, the intrepid traveler, on the 5 hour bus ride from Lijiang to our starting point. The hat was worn in anticipation of her 4-day stint as a cowgirl. Bei enjoyed the boisterous music videos that played on a drop-down screen at the front of an otherwise rattly bus as we bounced our way along winding dirt roads through the complex terrain of north Yunnan.

The bus stopped for a break in a small village along the road where a chaotic market clogged the streets. These four women were enjoying the scene and gossiping.

One of many pigs enjoying the good life in the streets of the village where we began our walk. As I've said before, right up until the point that they become dinner, pigs here lead a pretty enviable life. Their primary activites: sleeping in the sun, eating copiously and snorting at passers by. Something to aspire to.

Harvested branches against a basket in our starting village. We spent one night in this town before setting out and enjoyed wandering the narrow stone streets.

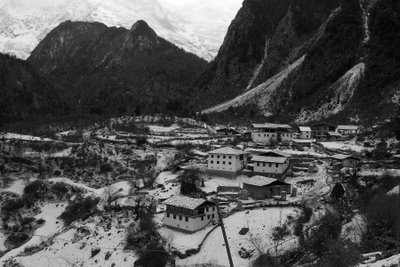

A typical Naxi village clinging to steep terraced slopes high above the Jinsha.

Ellen taking a break at the top of a pass on the first day of our walk. The trail climbed high above the river to avoid a precipitous gorge and by the time we reached this point we were knackered from the sun and the steep climb. Locals has blasted a 100 meter long tunnel through the very top of the pass to avoid a cliff that would have prevented further walking.

The Yangze River cuts a deep gorge through complex terrain. Jinsha means "gold sand" and is the Chinese name for the river here. Although this is the main upstream stem of the Yangze, I've also heard it referred to as a tributary.

Never call Jacqueline afraid of a little dirt. Here she plants herself face down on the dusty trail at the top of the pass.

A Naxi woman working in a winter wheat field near a village on the north side of the pass we hiked over on the first day.

Our group spread out along a typical stretch of trail on the first day. Bei is on our lone horse, happily chatting with whomever can keep up with her.

A woman in the late day sun near the house where we spent our first night. Each night was spent in a home guest house. This village was Naxi. There are about 275,000 Naxi people in Yunnan and they are concentrated around Lijiang, though Naxi villages are scattered throughout a broader area.

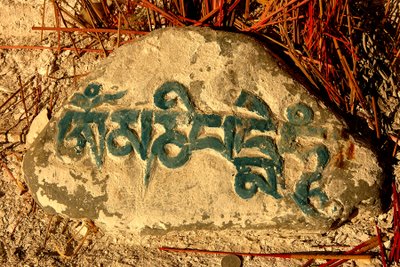

A wall at the bottom of the stairwell at our Naxi guest house on the first night.

Every bit of accessible land is subject to agriculture. Morning light on our second day highlights a small settlement atop a steep knob.

These two Naxi boys walked with us along the trail briefly on their way to some fields where others from their family were working.

A Naxi man on his way to work also shared the trail with us for a short while.

Bei on her horse during the second day. She joyfully rode for 8 hours or so each day without complaining.

Bei tests Jacqueline's sunglasses on our ferry ride across the Jinsha. The crossing point is destined to receive a bridge in the near future, which will change the nature of the villages on the other side. Although currently accessible by vehicle (from we know not where) the east side of the river here is still remote.

Crossing the Jinsha. Bei's horse climbed aboard the small, wooden boat with the rest of us and we set off, using eddies to minimize our downstream drift in the fast current.

A Mosuo boy in a village near where we spent our second night. The Mosuo are well known for their matrilineal society. Women own the family property here which is inherited by daughters rather than sons. The Mosuo people are also known for an institution known as "walking marriage" in which monogamous relationships are not required. A woman may have children by more than one man over the course of her life and marriage in our sense of the institution is not required. Many Mosuo do marry, but traditionally it has not been expected.

A one room dirt floored classroom near a small settlement high in the dry hills above the Jinsha on our third day.

Me enjoying the view high above the river on day 3. Our path began on the other side of the two small pointy bits of rock on the far side of the river on the distant skyline.

Ladles in the courtyard of a Mosuo house where we spent a night after our second day.

Farming paraphernalia on the roof of a Mosuo house where we ate lunch on our third day out.

The view south from our lunch spot on day 3. The Jinsha is in the steep gorge at center and our starting point was on the other side of the 2 pointy peaks in the far background.

Lunch on our third day. From left to right: Brian Collins (Seattle), Ellen and Bei, Devlin and Nicole (Australia) and Jacqueline Bishop (New Zealand).

A goat enjoys a rest in the courtyard of the house where we ate lunch.

Bei scoping out a baby goat playing on the roof of the Mosuo house where we had lunch.

After lunch we continued to climb away from the river, heading east towards a pass that would deliver us into the basin where our hike would end the next day. We stopped at a small store along the way where this poster decorated a door.

Our third night out was spent at a Pumi minority house. This was the most rustic of our accomodations on the trip--the weather had turned cold and threatening and we spent most of our time here in the kitchen, sitting on low stools around a warm fire in front of a Buddhist altar. Ellen traded English and Chinese with Mr. Mu, our guide on the trip, and with the couple that live in the house. I don't know a lot about the Pumi people, but the couple's daughter, who was away to study, left this note for visitors like ourselves:

"Welcome to my family. We are Pumi. Much to my regret many people don’t know Pumi. Pumi people are very kind, hardworking. We are Buddhist. Women aren’t allowed to kill animals. We respect God. Before meals, we should take the food we will get ready for eating to the God. If someone gives us sorrow, anger, trouble, etc., we will try our best to give his and her right way to treat others. We believe God will give us fairness. We have no written language. We should hand down custom, language, etc., from generation to generation by speaking and we know: In unity there is strength. We often help each other learn from each other and think of each other. Pumi Hangui culture is very interesting. What a pity I always study at school. I don’t know it all but if I have time I will study it and try my best to make more people know Pumi Hangui culture. My parents can sing all kinds of Pumi songs. You can listen to Pumi songs in my family. I will try my best to practice my spoken English. Next time I can introduce Pumi culture to you. If you want to make friends with me you can leave your address in my family. I hope you have a good time in my family." -- Helen Yang

Bei on the last day of the walk. It snowed up high during the night--just above where we slept, and we walked up into it the next morning, adding clothes as we went. Bei was the coldest, since the rest of us were working to climb the pass, and she happily donned Ellen's down jacket.

A Yi child above a poor village on the last day of our trip as we descended from the snowy pass back into dry country in a broad basin. Nearby this child's mother hacked at scrappy, sparse wood with an axe, a small child bundled on her back. Villages in this part of China have rights to cut wood in certain areas around their villages, and the forest near this village was decimated. Less than 50 years ago the Yi still raided villages of other minorities to take slaves. Though Yunnan ethnic groups coexist peacefully now, the Naxi still express some animosity towards the Yi.

Bicycles on the road to Yongning, the mid-sized town that was our end point. From Yongning we caught a minivan to Lugu Lake, and after a night there in a small hotel with wonderfully hot showers we rode a small bus back to Lijiang. A couple of weeks later Tony's brother and his friend Jenny did the same trip. On their return to Lijiang in a minivan, they sat in the back and several other people crowded into the front. Partway home, the front windshield of the van exploded into pieces and the woman in the front passenger seat began screaming. A football sized rock bouncing down the mountain had, against all odds, crashed through the windshield and landed on her lap, breaking her femur. Eventually, she was transported to the hospital in Lijiang.

Boats lining the shore of Lugu Hu. Lugu Hu until recently was remote and sparsely populated with small Mosuo villages. A new road and Chinese tourist development has reduced much of its appeal, though the lake itself is still pretty. If you are interested in the area and the Mosuo matrilineal culture, "Leaving Mother Lake," by Yang Erche Namu, is an excellent and very readable memoir about a woman who grew up here and went on to become a well known Chinese singer. In the book she describes her childhood in area around the lake and her family's history, including the effect of the Cultural Resolution even in remote parts of China like this.

Bei, the intrepid traveler, on the 5 hour bus ride from Lijiang to our starting point. The hat was worn in anticipation of her 4-day stint as a cowgirl. Bei enjoyed the boisterous music videos that played on a drop-down screen at the front of an otherwise rattly bus as we bounced our way along winding dirt roads through the complex terrain of north Yunnan.

The bus stopped for a break in a small village along the road where a chaotic market clogged the streets. These four women were enjoying the scene and gossiping.

One of many pigs enjoying the good life in the streets of the village where we began our walk. As I've said before, right up until the point that they become dinner, pigs here lead a pretty enviable life. Their primary activites: sleeping in the sun, eating copiously and snorting at passers by. Something to aspire to.

Harvested branches against a basket in our starting village. We spent one night in this town before setting out and enjoyed wandering the narrow stone streets.

A typical Naxi village clinging to steep terraced slopes high above the Jinsha.

Ellen taking a break at the top of a pass on the first day of our walk. The trail climbed high above the river to avoid a precipitous gorge and by the time we reached this point we were knackered from the sun and the steep climb. Locals has blasted a 100 meter long tunnel through the very top of the pass to avoid a cliff that would have prevented further walking.

The Yangze River cuts a deep gorge through complex terrain. Jinsha means "gold sand" and is the Chinese name for the river here. Although this is the main upstream stem of the Yangze, I've also heard it referred to as a tributary.

Never call Jacqueline afraid of a little dirt. Here she plants herself face down on the dusty trail at the top of the pass.

A Naxi woman working in a winter wheat field near a village on the north side of the pass we hiked over on the first day.

Our group spread out along a typical stretch of trail on the first day. Bei is on our lone horse, happily chatting with whomever can keep up with her.

A woman in the late day sun near the house where we spent our first night. Each night was spent in a home guest house. This village was Naxi. There are about 275,000 Naxi people in Yunnan and they are concentrated around Lijiang, though Naxi villages are scattered throughout a broader area.

A wall at the bottom of the stairwell at our Naxi guest house on the first night.

Every bit of accessible land is subject to agriculture. Morning light on our second day highlights a small settlement atop a steep knob.

These two Naxi boys walked with us along the trail briefly on their way to some fields where others from their family were working.

A Naxi man on his way to work also shared the trail with us for a short while.

Bei on her horse during the second day. She joyfully rode for 8 hours or so each day without complaining.

Bei tests Jacqueline's sunglasses on our ferry ride across the Jinsha. The crossing point is destined to receive a bridge in the near future, which will change the nature of the villages on the other side. Although currently accessible by vehicle (from we know not where) the east side of the river here is still remote.

Crossing the Jinsha. Bei's horse climbed aboard the small, wooden boat with the rest of us and we set off, using eddies to minimize our downstream drift in the fast current.

A Mosuo boy in a village near where we spent our second night. The Mosuo are well known for their matrilineal society. Women own the family property here which is inherited by daughters rather than sons. The Mosuo people are also known for an institution known as "walking marriage" in which monogamous relationships are not required. A woman may have children by more than one man over the course of her life and marriage in our sense of the institution is not required. Many Mosuo do marry, but traditionally it has not been expected.

A one room dirt floored classroom near a small settlement high in the dry hills above the Jinsha on our third day.

Me enjoying the view high above the river on day 3. Our path began on the other side of the two small pointy bits of rock on the far side of the river on the distant skyline.

Ladles in the courtyard of a Mosuo house where we spent a night after our second day.

Farming paraphernalia on the roof of a Mosuo house where we ate lunch on our third day out.

The view south from our lunch spot on day 3. The Jinsha is in the steep gorge at center and our starting point was on the other side of the 2 pointy peaks in the far background.

Lunch on our third day. From left to right: Brian Collins (Seattle), Ellen and Bei, Devlin and Nicole (Australia) and Jacqueline Bishop (New Zealand).

A goat enjoys a rest in the courtyard of the house where we ate lunch.

Bei scoping out a baby goat playing on the roof of the Mosuo house where we had lunch.

After lunch we continued to climb away from the river, heading east towards a pass that would deliver us into the basin where our hike would end the next day. We stopped at a small store along the way where this poster decorated a door.

Our third night out was spent at a Pumi minority house. This was the most rustic of our accomodations on the trip--the weather had turned cold and threatening and we spent most of our time here in the kitchen, sitting on low stools around a warm fire in front of a Buddhist altar. Ellen traded English and Chinese with Mr. Mu, our guide on the trip, and with the couple that live in the house. I don't know a lot about the Pumi people, but the couple's daughter, who was away to study, left this note for visitors like ourselves:

"Welcome to my family. We are Pumi. Much to my regret many people don’t know Pumi. Pumi people are very kind, hardworking. We are Buddhist. Women aren’t allowed to kill animals. We respect God. Before meals, we should take the food we will get ready for eating to the God. If someone gives us sorrow, anger, trouble, etc., we will try our best to give his and her right way to treat others. We believe God will give us fairness. We have no written language. We should hand down custom, language, etc., from generation to generation by speaking and we know: In unity there is strength. We often help each other learn from each other and think of each other. Pumi Hangui culture is very interesting. What a pity I always study at school. I don’t know it all but if I have time I will study it and try my best to make more people know Pumi Hangui culture. My parents can sing all kinds of Pumi songs. You can listen to Pumi songs in my family. I will try my best to practice my spoken English. Next time I can introduce Pumi culture to you. If you want to make friends with me you can leave your address in my family. I hope you have a good time in my family." -- Helen Yang

Bei on the last day of the walk. It snowed up high during the night--just above where we slept, and we walked up into it the next morning, adding clothes as we went. Bei was the coldest, since the rest of us were working to climb the pass, and she happily donned Ellen's down jacket.

A Yi child above a poor village on the last day of our trip as we descended from the snowy pass back into dry country in a broad basin. Nearby this child's mother hacked at scrappy, sparse wood with an axe, a small child bundled on her back. Villages in this part of China have rights to cut wood in certain areas around their villages, and the forest near this village was decimated. Less than 50 years ago the Yi still raided villages of other minorities to take slaves. Though Yunnan ethnic groups coexist peacefully now, the Naxi still express some animosity towards the Yi.

Bicycles on the road to Yongning, the mid-sized town that was our end point. From Yongning we caught a minivan to Lugu Lake, and after a night there in a small hotel with wonderfully hot showers we rode a small bus back to Lijiang. A couple of weeks later Tony's brother and his friend Jenny did the same trip. On their return to Lijiang in a minivan, they sat in the back and several other people crowded into the front. Partway home, the front windshield of the van exploded into pieces and the woman in the front passenger seat began screaming. A football sized rock bouncing down the mountain had, against all odds, crashed through the windshield and landed on her lap, breaking her femur. Eventually, she was transported to the hospital in Lijiang.

Boats lining the shore of Lugu Hu. Lugu Hu until recently was remote and sparsely populated with small Mosuo villages. A new road and Chinese tourist development has reduced much of its appeal, though the lake itself is still pretty. If you are interested in the area and the Mosuo matrilineal culture, "Leaving Mother Lake," by Yang Erche Namu, is an excellent and very readable memoir about a woman who grew up here and went on to become a well known Chinese singer. In the book she describes her childhood in area around the lake and her family's history, including the effect of the Cultural Resolution even in remote parts of China like this.