Adoption in China - Revising Life Stories

27 October 2005

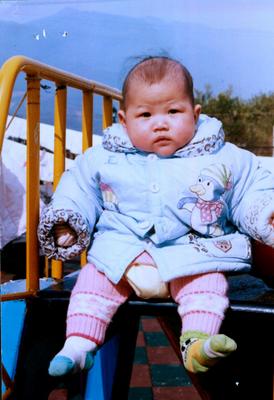

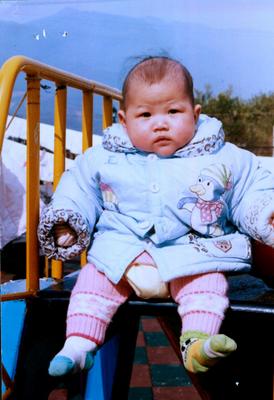

Bei (then Gan Feng Jie) at the Social Welfare Institute in Feng Cheng City in late 2001 or early 2002 (photo taken by the SWI).

Bei (back right in pink shirt) with other kids at the Social Welfare Institute (photo taken by the SWI).

Part of our motivation for coming to China this year was, of course, that China is our daughter Bei’s home country. The Chinese are immensely curious about Bei and they are surprisingly confused when they see her with us—two obviously white parents. There is little shyness in China about staring, and people stand on the street looking back and forth from Bei to Ellen to me in confusion. If it is just one of us with Bei they may ask if the absent parent is Chinese. The relief of understanding a mystery leaps onto their faces when we tell them that Bei is adopted (“Ta shi shou yang de.” – “She is adopted.”) and the reaction is always a thumbs-up or an expression of how lucky Bei is, to which we reply that we are the lucky ones.

Curious kids crowd around Bei in Feng Cheng after her adoption to inspect a Chinese girl with obviously foreign parents.

During our train ride from Shanghai to Kunming we passed directly through Bei’s hometown just after dawn on a dreary Sunday morning. Feng Cheng is a small, nondescript, typical southeastern Chinese city, with concrete apartment buildings and stores surrounded by rice paddies and, in this part of the Jiangxi Province, coal mines. Evenly spaced trees line the highway that follows the railroad tracks, and a few trucks and bicycles moved along it in the early morning. I snapped some blurry photos through the train window to save for Bei, who was still sleeping.

Feng Cheng City at dawn on a rainy day, viewed through the train window.

In one field I saw a man with a little girl about Bei’s age and, as we passed, he hoisted her onto his shoulders for the walk back into town, much as we often carry Bei when she is too tired to walk. I couldn’t help but think about how easily Bei could have been that girl, living an utterly different life in China, instead of sleeping through the dawn in a soft sleeper train bed with two American parents. And I couldn’t help but imagine that somewhere in that town, maybe even within sight of the rail line, Bei’s birth mother was busy making breakfast, unaware that the one-day old girl she had left at a Feng Cheng school gate in 2001 was passing through town and dreaming four year old dreams in English.

It is not just foreigners who adopt children in China, and it has been interesting to learn that adoption here is viewed quite differently than it is in the U.S. One of the most surprising things that we have discovered, initially through conversations with our friend Wei Hong in Shanghai (the wife of our American instructor there), is that in China adoption is often a huge secret kept from the adoptive child for as long as possible. In fact, it isn’t a stretch to imagine adopted people living their entire lives here without ever knowing that they were adopted. And remarkably, according to Wei Hong, who has an adopted cousin, everyone else in the family and in the family’s social circle except the adopted child knows the truth.

Of course our philosophy in the U.S. about sharing the adoption story (domestic or foreign) is quite the opposite—we start talking about adoption and birth parents from the earliest opportunity so that it isn't a big surprise for the child. Our thinking is that if the child is aware of adoption from the beginning, they integrate this identity as they grow up with their adoptive parents and they avoid dealing with an unanticipated sea change in the context of their lives upon discovery of their history. And of course there is an implicit understanding by us that adoption is not shameful or something to be hidden away.

So why do the Chinese take the opposite approach—hiding this enormous truth, a huge elephant in the closet?? I can speculate based on a few conversations, some reading and the results of an assignment that I gave my second year writing students here in Lijiang.

An obvious hypothesis is that there is a sense of shame in China about adoption—aren’t big secrets often related to a need to hide something shameful? But if this were the case, why would everyone except the child be let in on the secret? This suggests that perhaps the parents are not themselves ashamed, but feel that the child’s very history might be shameful for the child. To them, keeping the truth a secret may be a design to protect the child.

One could imagine that protecting the child from shame by keeping the secret may have something to do with trying to save “face” for the adopted child. The concept of face in China is more important than it is for us in the U.S. (though we have it), and perhaps there is a belief here that an adopted child would experience a loss of face upon finding out about her history. This does not seem a huge stretch. In the book, “Encountering the Chinese – A Guide for Americans,” the authors (Hu and Grove, 1999) put it this way:

But does this really apply to the dilemma of whether to tell a child about adoption or to keep it a secret? It seems to me that if a child’s identity includes early knowledge of adoption, then there is no issue of “face” since there would be no catastrophic change of self image (loss of face) for the child within the child’s family and social group upon revelation of her story. So maybe this concept doesn’t explain the issue after all.

An explanation offered by Wei Hong for the secrecy in her family was that the parents feared that if a child knew she was adopted, she might love her parents less. This viewpoint is supported by at least some of the students in my classes who, aside from representing the relatively rare slice of the Chinese population that goes to college, come from all over the China and offer a geographic cross-section of Chinese thinking among their generation.

Ying Zhou Na, a writing student, explains it like this (unedited):

Wang Hai Lian writes (again, unedited):

This, of course, implies that the truth about adoption, while fundamentally devastating, can perhaps be swallowed when a person grows to maturity with the strength built upon the foundation of an idyllic childhood. The majority of students felt that eventually, an adoptee should be told the truth. When pressed, they surmised that “eventually” meant when they were fully mature adults.

Sui Shanru summed this view up like this:

As westerners steeped in individualism we have confidence in the strength of our children and in their ability to grow strong in the shelter of our love, with full knowledge of their adoption histories. Life books, adoption stories, heritage camps and early musings about birth mothers are part of our roadmap. And of course for us, this system feels like the right path. And I think it is. But as I glimpsed the little girl and her father, walking home between rice paddies outside of Feng Cheng in southeastern China, how could I to know what her life might be like? For me and Ellen and Bei, the train left Feng Cheng on it’s way west to a different life.

Bei in Tiger Leaping Gorge.

Bei (then Gan Feng Jie) at the Social Welfare Institute in Feng Cheng City in late 2001 or early 2002 (photo taken by the SWI).

Bei (back right in pink shirt) with other kids at the Social Welfare Institute (photo taken by the SWI).

Part of our motivation for coming to China this year was, of course, that China is our daughter Bei’s home country. The Chinese are immensely curious about Bei and they are surprisingly confused when they see her with us—two obviously white parents. There is little shyness in China about staring, and people stand on the street looking back and forth from Bei to Ellen to me in confusion. If it is just one of us with Bei they may ask if the absent parent is Chinese. The relief of understanding a mystery leaps onto their faces when we tell them that Bei is adopted (“Ta shi shou yang de.” – “She is adopted.”) and the reaction is always a thumbs-up or an expression of how lucky Bei is, to which we reply that we are the lucky ones.

Curious kids crowd around Bei in Feng Cheng after her adoption to inspect a Chinese girl with obviously foreign parents.

During our train ride from Shanghai to Kunming we passed directly through Bei’s hometown just after dawn on a dreary Sunday morning. Feng Cheng is a small, nondescript, typical southeastern Chinese city, with concrete apartment buildings and stores surrounded by rice paddies and, in this part of the Jiangxi Province, coal mines. Evenly spaced trees line the highway that follows the railroad tracks, and a few trucks and bicycles moved along it in the early morning. I snapped some blurry photos through the train window to save for Bei, who was still sleeping.

Feng Cheng City at dawn on a rainy day, viewed through the train window.

In one field I saw a man with a little girl about Bei’s age and, as we passed, he hoisted her onto his shoulders for the walk back into town, much as we often carry Bei when she is too tired to walk. I couldn’t help but think about how easily Bei could have been that girl, living an utterly different life in China, instead of sleeping through the dawn in a soft sleeper train bed with two American parents. And I couldn’t help but imagine that somewhere in that town, maybe even within sight of the rail line, Bei’s birth mother was busy making breakfast, unaware that the one-day old girl she had left at a Feng Cheng school gate in 2001 was passing through town and dreaming four year old dreams in English.

It is not just foreigners who adopt children in China, and it has been interesting to learn that adoption here is viewed quite differently than it is in the U.S. One of the most surprising things that we have discovered, initially through conversations with our friend Wei Hong in Shanghai (the wife of our American instructor there), is that in China adoption is often a huge secret kept from the adoptive child for as long as possible. In fact, it isn’t a stretch to imagine adopted people living their entire lives here without ever knowing that they were adopted. And remarkably, according to Wei Hong, who has an adopted cousin, everyone else in the family and in the family’s social circle except the adopted child knows the truth.

Of course our philosophy in the U.S. about sharing the adoption story (domestic or foreign) is quite the opposite—we start talking about adoption and birth parents from the earliest opportunity so that it isn't a big surprise for the child. Our thinking is that if the child is aware of adoption from the beginning, they integrate this identity as they grow up with their adoptive parents and they avoid dealing with an unanticipated sea change in the context of their lives upon discovery of their history. And of course there is an implicit understanding by us that adoption is not shameful or something to be hidden away.

So why do the Chinese take the opposite approach—hiding this enormous truth, a huge elephant in the closet?? I can speculate based on a few conversations, some reading and the results of an assignment that I gave my second year writing students here in Lijiang.

An obvious hypothesis is that there is a sense of shame in China about adoption—aren’t big secrets often related to a need to hide something shameful? But if this were the case, why would everyone except the child be let in on the secret? This suggests that perhaps the parents are not themselves ashamed, but feel that the child’s very history might be shameful for the child. To them, keeping the truth a secret may be a design to protect the child.

One could imagine that protecting the child from shame by keeping the secret may have something to do with trying to save “face” for the adopted child. The concept of face in China is more important than it is for us in the U.S. (though we have it), and perhaps there is a belief here that an adopted child would experience a loss of face upon finding out about her history. This does not seem a huge stretch. In the book, “Encountering the Chinese – A Guide for Americans,” the authors (Hu and Grove, 1999) put it this way:

As people grow into adulthood, they gradually adopt certain claims regarding their own characteristics and traits, and they learn to make these claims, implicitly and sometimes explicitly, to others. People also learn to recognize other individuals’ implicit claims about themselves and to accept (or in some cases to appear to accept) those claims…This set of claims, or line, of each person is his or her face.Face is important in China because of the nature of society here (according to Hu and Grove). In contrast to the relatively transient social relationships in the U.S. and some other western countries, the Chinese are strongly tied to their families and social groups for their entire lives, with relatively less mobility than us. As a result, it is critical to maintain these relationships, which means maintaining a stable self image – “face.” In a sense, losing face means losing status in your entire social support group – almost like being exiled.

But does this really apply to the dilemma of whether to tell a child about adoption or to keep it a secret? It seems to me that if a child’s identity includes early knowledge of adoption, then there is no issue of “face” since there would be no catastrophic change of self image (loss of face) for the child within the child’s family and social group upon revelation of her story. So maybe this concept doesn’t explain the issue after all.

An explanation offered by Wei Hong for the secrecy in her family was that the parents feared that if a child knew she was adopted, she might love her parents less. This viewpoint is supported by at least some of the students in my classes who, aside from representing the relatively rare slice of the Chinese population that goes to college, come from all over the China and offer a geographic cross-section of Chinese thinking among their generation.

Ying Zhou Na, a writing student, explains it like this (unedited):

If I adopt a child, I won’t tell her that she is adopted. I think it is not necessary to tell her who are her birth parents. I also can give her a warm family, as good as her birth parents could do. I’m afraid that she will be sad at hearing the news that she is adopted. She may keep silent to us later. To keep secret to her is better than to tell her the truth, I believe. Personally speaking, I don’t want to tell her the truth either. As I consider that it may affect our close relationship.The writing is a little clumsy, but you get the idea. And this sentiment was expressed by many students in my classes. But other students refute this and suggest another reason for keeping secrets that seems to come closer to the heart of the issue for the Chinese I’ve talked with.

Wang Hai Lian writes (again, unedited):

By tradition, Chinese parents always not tell their adopted children who are adopted. It is not because they are afraid the adopted children loved them less, but it will be hurt the children’s heart and do harmful of children’s growth. In my opinion, if the family have several children who are birth children and adopted children, the parents should not have to tell the child who are adopted. If the family have only adopted child, maybe they have lots of adopted child, the parents should have had to tell the children. Even if the children and parents were become close friends maybe child could keep touch with birth parent but they always loved and close with their adoptive parents. I known my uncle have two daughter. So he give his little daughter to other people who haven’t child. After fourteen years, my uncle went to her home and wanted her called him father. I don’t know when her adopted parents told her that she were a adopted child, but her only told my uncle: “I only have one family and one parents. I never know you and never wants to know you.”Many students shared this opinion. To tell a young child the truth about adoption would break the child’s spirit and taint their view of the world. All children should see their world as a beautiful and happy place with no lurking shadows to darken their days. To these students the illusion of a perfect world for a child is the most important thing. This central philosophy of a sacred happy childhood was repeated in paper after paper as well as in class discussions. When a child is young, their ability to cope is low and adoption truth could be catastrophic.

This, of course, implies that the truth about adoption, while fundamentally devastating, can perhaps be swallowed when a person grows to maturity with the strength built upon the foundation of an idyllic childhood. The majority of students felt that eventually, an adoptee should be told the truth. When pressed, they surmised that “eventually” meant when they were fully mature adults.

Sui Shanru summed this view up like this:

I think adoptive parents should tell their child that she is adopted when she is old enough. After all, the adoption is a fact that they must face. So, we must tell them. But we must choose a suitable time at the same time. Because, in my opinion, they are pure when they are young. They should live happily. We should make them believe that the world is wonderful. The persons around them are kind and love them. I also think a little child don’t have the ability to distinguish right and wrong. They are easy to do something wrong. If they know the fact early, they may be self-abased. And they will think, “Why my birth parents abandoned me?” So they will give up themselves. They can’t understand even though their birth parents had some difficulties that they are reluctant to discuss or mention. So, as for this question, I think the adoptive parents should tell their child that she is adopted when they grow old enough to think deeply.Hou Jun Ping from the Gansu Province agrees:

For my part, I think adoptive parents should tell their child the truth. The child has the right to know everything about himself. If I were a adoptive mother, I would tell my child he is adopted. I won’t tell him when he is young. One of my aunt’s daughters was adopted at 2 years old by another aunt. My aunt is kind to her and kept the secret for a long time. At last, my aunt told my adopted cousin the truth. My cousin said, “Mum, I knew I’m not your birth daughter early, then I was unhappy. Now I understand you. I’m your birth daughter and you are my birth mother.” Now my cousin has two [sets of] parents. She lives a happy life. The adoptive parents should tell their child that she is adopted.But an adopted girl, Peng Yan, from one of my writing classes, refuted many of the arguments of her peers:

In my opinion, adoptive parents should tell their children that they are adopted. Because when they grow up to be a teen, they must think lots of things that making them very sad. But if they told their children the truth when they were a small child, it might be a habit: [become internalized] they know they are adopted but they don’t care.

It is just my opinion, because I am a adopted child, too. I was very young. I learned the truth by my mother. Although sometimes I am sad that I was adopted, I knew that my adoptive parents love me very much, especially my mother. She makes me very happy and I don’t feel different with others. I appreciate her of course. I love them as if they are my birth parents.Zhang Lu Yan supports this idea but describes a more ambitious course of moral and political development for her future adopted child, a “brave boy”:

If I had an adopted child, I would tell him that he was adopted. I said “he” because I had a wish that one day I could adopt an African boy. I want to adopt an African boy because there are many kids homeless and ill or starve to death everyday in Africa. I want to adopt a boy because I think boys are more brave than girls. I will teach him everything when he is young. I want him to be tough-minded. I want him to be responsible. I want him to have strong self-respect. So I teach him at his youth. When he grows up he should be prepared to face himself, to face his country and to devote to his country. Thus, I will tell him that he is adopted with no hesitation. It’s my choice to adopt him, but it’s his choice to decide what he can do to the world when he can rely on his own effort.

As westerners steeped in individualism we have confidence in the strength of our children and in their ability to grow strong in the shelter of our love, with full knowledge of their adoption histories. Life books, adoption stories, heritage camps and early musings about birth mothers are part of our roadmap. And of course for us, this system feels like the right path. And I think it is. But as I glimpsed the little girl and her father, walking home between rice paddies outside of Feng Cheng in southeastern China, how could I to know what her life might be like? For me and Ellen and Bei, the train left Feng Cheng on it’s way west to a different life.

Bei in Tiger Leaping Gorge.