Yes We Work Too (Teaching)

29 March 2006

Alone with a frightened student in a cold stark classroom under flickering fluorescent lights, an encouraging smile pasted on your face, you grasp desperately for a limited palette of simple, understandable (and boring as hell) oral exam topics. The too obvious choice is “tell me about your hometown” and you fall back on it over and over again. Your body tenses in anticipation of the inevitable answer, delivered in an accent so thick that you strain to understand:

“My hometown is very beautiful!! The food is delicious!! The people are friendly!! Welcome to my hometown!!!” (though the student’s home is at least 36 train hours away).

Mixing that “conversation” with weak Chinese beer on evenings after exams produces satisfying revisions. In a recent e-mail I teased our friend Tony, who until two weeks ago taught here with us but bailed to his native Australia in part to fulfill a 50th birthday resolution to “avoid jobs that feel hopeless”:

...Ironically, the Oral English students reported today that they previously had been "taking the piss" out of the foreign teachers when in truth they "speak a refined formal English that is a hybridized but jaunty combination of American, Australian and British dialects with an occasional naughty Sino-English twist of phrase" (in their words). The students went on to say that "now that we've 'weeded the garden' of less committed foreign teachers [Tony] we are ready to get down to business and engage in a discourse from which a real cultural and international understanding can be reaped, much like the local peasants reap winter wheat from their verdant fields."

We all had a good laugh together about their ingenious use of tired clichés as tools for driving foreign teachers to distraction. "The food in my hometown sucks and the people are real bastards," one student reported, laughing. "And there's so much friggin' pollution that you can barely see the mindless sprawl of white tile and blue glass communist-style buildings." He went on: "If my mother could cook, maybe I'd go back, but she can’t even boil water. I'm outta there for life. Welcome to shit!"

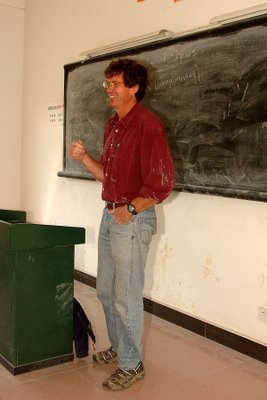

Second year English majors taking a vocabulary exam.

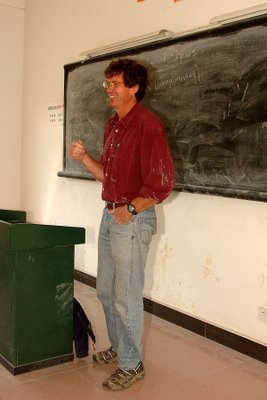

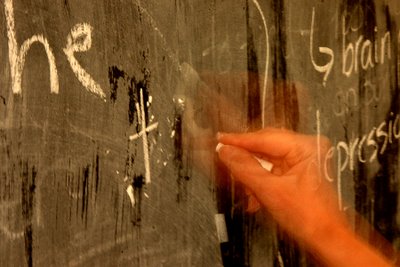

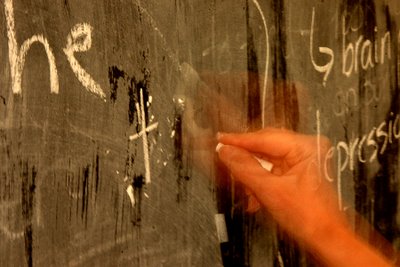

Teaching at the Lijiang Culture and Tourism College. This multi-media classroom features...a blackboard. And chalk that breaks every time you try to write. The blackboard itself is a rough piece of slate that was painted black to make it look more like a blackboard.

Our college, the Lijiang Culture and Tourism College of Yunnan University (try writing that in Chinese and you’ll understand why the college doesn’t sell many sweatshirts) is an unusual product of China’s changing society in that it is a privately managed business with only loose ties to the public Yunnan University in Kunming. Students here have had the misfortune of failing their college entrance exams and therefore losing the opportunity to attend first- or second-tier colleges in bigger cities. Many of these students failed for reasons like 1) extreme slacker-ness, 2) refusal to study while getting their hair puffed up, 3) unwillingness to give up their hobbies -- watching TV and sleeping, or 4) devotion to attaining personal-best scores on their favorite computer games. These are the students who come from beautiful, delicious, friendly hometowns—the ones who sit in the back of the room, talking to each other or looking at their ever-lengthening fingernails while us teachers try to find a way to give the other 30 - 50 students a chance to learn something new about using English.

As one slacker wrote last semester:

“I like to learn English, but I’m always lazy to increasing my English vocabulary. I think it’s very difficult. But I’ll try my best in learning English. And I hate cockroach very much.”

Others, in response to an exercise where I asked the students to close their eyes and sit in silence for 1-minute and then write about their thoughts, provided this scintillating window into their lives:

“Just now I closed my eyes for one minute. In this moment, I found one minute is a really long time. You can think a lot of things.”

“I just counted numbers from one to seventy-eight. Nothing to think only taking a rest of my eyes.”

“I think nothing but count the seconds when I close my eyes.”

“When I closed my eyes I found myself in a dark world that is so lonely.”

Honest, but not terribly encouraging in terms of getting students to be creative, though perhaps the last one has possibilities.

In fairness, other students were somewhat more interesting...and psychotic:

“When I closed my eyes I imagine I was in a very beautiful world. In the world a river run through a bridge and to a grand castle. I was stood on the edge of the castle and looking to the end of the sky. Suddenly, a very huge and horrible devil was flying to my land, I picked up my sword and fight with the devil.”

Teaching English as a Second Language (ESL) at a school like this is a little like trying to get George Bush to use big words correctly. Even a well qualified team of “handlers” can expect a lot of repetitive exercises, some serious screw-ups and no shortage of “misunderestimated” frustration.

The system itself is self-defeating. As Tony put it only half-jokingly before he left: “student grade sheets have three columns—the student’s academic mark, their parent’s income and their final grade.” Cynical, but not far from the truth. Students who pay the tuition do not fail no matter how poorly they do academically. Students who never attend class and fail are given the opportunity to take a 5-minute makeup exam (oral) by a different teacher from the one who failed them, and if they survive that they pass the entire course. If they fail this makeup exam, the school still has the ultimate last word, and the kids are almost always passed. The system amounts to a pay-for-a-degree program requiring 4 years of tuition. Merit is not crucial. As a teacher, it can make you crazy.

In China failing the college entrance exam usually means not only no college but also a bad job...unless you can find a school like ours that, though not high on the academic totem pole, accepts students who cobble together the extravagant tuition and buy their way in. Ten-thousand yuan a year (about $1250 USD)–a small fortune for many Chinese—is the cost for one year at our school, compared with much lower fees at academically better, state-run institutions in big cities like Beijing, Tianjin or Nanjing.

Not all of the students here have rich parents. Some come from poor farming families who struggle immensely to send their kids to this college. It is to protect these students that we come down harder on the insolent kids that don’t apply themselves because they have never had to. I have kicked kids out of class in China for misbehavior, something I have never done in the U.S. It is necessary if you want to give the hard workers a chance—ones like the students who wrote these passages about their home life:

“In 2002 my father leaved home and drove a bus in a village. He began to live by himself with no good friends, no TV and no normal power. I think he often felt alone. He always went to bed at eight if the bus needn’t repair. He didn’t enjoy the Spring Festival with us for four years.

During this time [this year’s holiday] my sister and I went to the village. We accompanied our father to spend more happy time. I always help my father to wash the bus. If he will repair, I would help him at any moment. I didn’t talk a lot with my father [before this holiday], but we talk far more in Spring Festival. We talked about my future, the farm work, and the others. We changed different ideas, had a good talk. We are believed each other. We are understand each other. I think that was very important for this winter vacation. I have a good time in this Spring Festival because I spend more time with my father and help him do more work”

"First I miss my mother. She is very warm hearted even though she has the hot temper, but she loves me very much. She often told me something about what I should do. I miss her everyday. I miss my father too. There are four children in my family. My brother sister and I are students. Every day we cost so much. In order to let us study, my father work day and night. I think he is the great man in the world. I love and miss he very much. I can use word to express my feeling. Every day he told me study hard."

Also, unlike George Bush, many of the students are genuinely nice and it’s often the poorest students, the ones whose families are living hard so that their child can get a better education, that are the most generous and motivated. These are the students that make it worth trying to do a good job and these are the ones that say “welcome to my hometown” not to fill dead air, but because they are desperate to show you how they live and how generous their families can be.

“I was born in a poor village, 1980s. My family was poor, too. One day, it was dark but my parents still working hard on the farm. My sister and I couldn’t stay at home because there was no lights (our countryside was no electricity at that time). We were sitting at a corner of the ground of my house and crying. About half an hour past, my parents came back. They lighted the oil lighter. I saw their clothes was so broken, then I went to the corner and crying again. I pledged to be a useful man in the future. I must study hard.”

The educational system is much different in China than in the U.S. too (though increasingly we Americans also ‘teach to the test’). To some extent, one understands the predisposition for coasting among students who, as children, attend primary school from 7:30 a.m. until 5 p.m. and then stay up until 9 or 10 at night doing mandatory homework. College for many of these kids is a time to relax and have fun, far from the pressures of senior middle school (though they are often homesick).

My understanding of education in China is that students struggle through primary, junior and senior middle school in anticipation of the feared college entrance exam which is taken during their senior years. The entire system focuses on preparing the kids for a battery of standardized tests that they take periodically throughout their school years. It’s no wonder that kids are sick of study by the time they reach college. As one of our Chinese friends here put it (while her 10-year old studied), “nobody here likes the system but nobody changes it.”

One student described school life like this:

“Many years ago when I still studied in primary school, I lived through a very ‘hard life.’ Because my mother was a severe person and my father was more severe than her.

Therefore, they told me the first thing when I back home from school is study. I must have good scores on the exam, otherwise I would be blamed. So I had few time to play with my friends.

One day, my father taught me Chinese pinyin. I read it ‘p,’ but my father said the opposite so he thought it was “b.” So he yelled to me. ‘So fool mistake.’ I was so sad and cried. Fortunately my mother found the reason and told my father. After a few minutes silence, my father told me: ‘you can play all day.’

That day was one of my happiest days in my childhood.

China’s educational philosophy hinges on the importance of rote knowledge frequently at the expense of individual problem solving and critical thinking. We jokingly refer to “the collective brain” in our classes where correct answers can be dredged out of the class as a whole, but few individual students do well on, say, a simple vocabulary test.

I read an article recently (I can’t recall where and I don’t have copy of it in my notes) that said that although Chinese students often excel at math and science in school, they fail to achieve a proportionate level of success in their careers (for example publishing in prestigious journals, winning Nobel prizes, etc.) because, the article surmised, on the whole they lack the creativity and independence in their thinking that leads research in new directions and bears professional fruit.

Peter Hessler, in his book “River Town” describing his experience teaching in Sichuan in 1996, was frustrated by the lack of individual thought regarding the then impending return of Hong Kong to China. Paradoxically, he discovered that uneducated people in Fuling, where he taught, were more likely to have an original point of view than his better educated students:

“Two or three times a week I stopped to chat with Ke Xianlong, the forty-seven-year-old photographer in South Mountain Gate Park, and the more I got to know him the more I was surprised at his political views. He was completely uneducated but he had interesting ideas; sometimes he talked about the need for more democracy and other political parties, and these were views I never heard on campus...

I realized that as a thinking person his advantage lay precisely in his lack of formal education. Nobody told him what to think, and thus he was free to think clearly.

It wasn’t the sort of revelation that inspires a teacher. The more I thought about this, the more pessimistic I was about the education that my students were receiving, and I began to feel increasingly ambivalent about teaching in a place like that...”

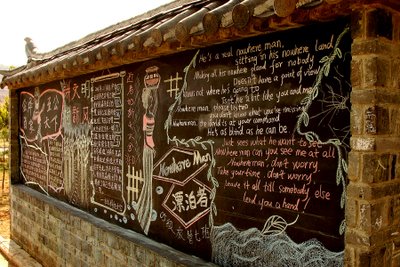

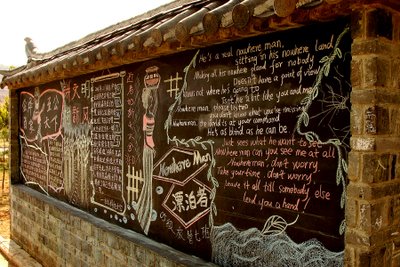

There are blackboards outside of the classroom buildings on our campus where each semester students from different classes (students pass through college as a member of a single class of 35-60 students that take all of the same classes together) paint or use colored chalk to express themselves on whatever topics they choose (and they choose some odd topics). Ironically this semester, outside of the main classroom building, a class insightfully (or randomly??) chose the lyrics from “Nowhere Man” for their board:

He's a real nowhere man,

Sitting in his nowhere land,

Making all his nowhere plans

for nobody.

Doesn't have a point of view,

Knows not where he's going to,

Isn't he a bit like you and me?

After a hard day in class trying to get students to actually debate two sides of a topic, this message brings a bit of wry comical relief.

The Nowhere Man class chalkboard outside one of the classroom buildings.

Sometimes the lack of critical thinking can be infuriating. In response to a midterm exam question asking whether students thought that gay marriage should be allowed in China, one of my students wrote (unfortunately, I don’t have the exact quotation) that China is very susceptible to fashion trends and that since being gay might be seen as fashionable, if gay marriage were allowed all Chinese might decide to become gay, thereby ensuring the demise of China since there would be no next generation (because gays can’t have children).

I’m not kidding. That was from a 20-something-year-old second-year college student on a midterm exam.

Hessler, who usually had an admirably optimistic attitude about his teaching, wrote:

“...I realized that I was not teaching forty-five individual students with forty-five individual ideas. I was teaching a group, and these were moments when the group thought as one, and a group like that was a mob, even if it was silent and passive.”

So teaching here is a daily struggle between a sense of ineffectiveness and frustration on the one hand and responsibility to the twenty percent or so of the students who are motivated to learn on the other. For Ellen and me, being here is enough of a reward and teaching is the price we pay, so we make of it what we can. There are good days and bad days. As students have said in "position" papers: “every sword has two blades.” (??!!)

Ellen writes on the blackboard with self-destructing chalk. In a two hour class one typically uses 10-15 pieces of chalk.

And in truth, though it’s fun to wax cynical, I’m not complaining. Really. Each foreign teacher at our college is responsible for 14 classroom hours per week. For me that means five two-hour Oral English courses for non-English majors and two two-hour writing courses for English majors—altogether about 350 students. The writing courses are fun, and I feel like I accomplish something with the students, who are more motivated than the non-English majors. In the end, it amounts to only a 20-25 hour work week with lots of free time. Not at all a bad way to reside in a place like northern Yunnan, where a 2-hour bike ride can take you through villages that people fly halfway around the world to see.

And when we feel the most cynical, we go back and read what these nineteen to twenty-year-old kids write, sometimes for the humorous mistakes but more often to remind ourselves about how amazingly comfortable our lives are in the U.S., while much of the rest of the world still struggles.

Dear Ellen,

I’m Kid. Glad to write to you.

I’ve come [been] here for one month. I thought everything [would be] here, including my future. But the fact make me feel intimidate.

I come from a small village. You know, most of villages in China are not very well. As many students, I used to work on the farm for few years. There are only ten boys got access to the college for their future education in our country [region] this September. As a lucky dog, I felt very happy. But after a month’s classes I found that many students were not very serious with the study and their English was very poor. What a bad luck! Luckily, I am not the one in them. After a six years study I have learned most of the basic grammar, words (few) we use everyday.

You know, learning a foreign language is difficult for a foreigner. Like you and me. But now I think I have hope. Because I meet you. The God is great. He arrange us meet here.

So I will not quit.

Alone with a frightened student in a cold stark classroom under flickering fluorescent lights, an encouraging smile pasted on your face, you grasp desperately for a limited palette of simple, understandable (and boring as hell) oral exam topics. The too obvious choice is “tell me about your hometown” and you fall back on it over and over again. Your body tenses in anticipation of the inevitable answer, delivered in an accent so thick that you strain to understand:

“My hometown is very beautiful!! The food is delicious!! The people are friendly!! Welcome to my hometown!!!” (though the student’s home is at least 36 train hours away).

Mixing that “conversation” with weak Chinese beer on evenings after exams produces satisfying revisions. In a recent e-mail I teased our friend Tony, who until two weeks ago taught here with us but bailed to his native Australia in part to fulfill a 50th birthday resolution to “avoid jobs that feel hopeless”:

...Ironically, the Oral English students reported today that they previously had been "taking the piss" out of the foreign teachers when in truth they "speak a refined formal English that is a hybridized but jaunty combination of American, Australian and British dialects with an occasional naughty Sino-English twist of phrase" (in their words). The students went on to say that "now that we've 'weeded the garden' of less committed foreign teachers [Tony] we are ready to get down to business and engage in a discourse from which a real cultural and international understanding can be reaped, much like the local peasants reap winter wheat from their verdant fields."

We all had a good laugh together about their ingenious use of tired clichés as tools for driving foreign teachers to distraction. "The food in my hometown sucks and the people are real bastards," one student reported, laughing. "And there's so much friggin' pollution that you can barely see the mindless sprawl of white tile and blue glass communist-style buildings." He went on: "If my mother could cook, maybe I'd go back, but she can’t even boil water. I'm outta there for life. Welcome to shit!"

Second year English majors taking a vocabulary exam.

Teaching at the Lijiang Culture and Tourism College. This multi-media classroom features...a blackboard. And chalk that breaks every time you try to write. The blackboard itself is a rough piece of slate that was painted black to make it look more like a blackboard.

Our college, the Lijiang Culture and Tourism College of Yunnan University (try writing that in Chinese and you’ll understand why the college doesn’t sell many sweatshirts) is an unusual product of China’s changing society in that it is a privately managed business with only loose ties to the public Yunnan University in Kunming. Students here have had the misfortune of failing their college entrance exams and therefore losing the opportunity to attend first- or second-tier colleges in bigger cities. Many of these students failed for reasons like 1) extreme slacker-ness, 2) refusal to study while getting their hair puffed up, 3) unwillingness to give up their hobbies -- watching TV and sleeping, or 4) devotion to attaining personal-best scores on their favorite computer games. These are the students who come from beautiful, delicious, friendly hometowns—the ones who sit in the back of the room, talking to each other or looking at their ever-lengthening fingernails while us teachers try to find a way to give the other 30 - 50 students a chance to learn something new about using English.

As one slacker wrote last semester:

“I like to learn English, but I’m always lazy to increasing my English vocabulary. I think it’s very difficult. But I’ll try my best in learning English. And I hate cockroach very much.”

Others, in response to an exercise where I asked the students to close their eyes and sit in silence for 1-minute and then write about their thoughts, provided this scintillating window into their lives:

“Just now I closed my eyes for one minute. In this moment, I found one minute is a really long time. You can think a lot of things.”

“I just counted numbers from one to seventy-eight. Nothing to think only taking a rest of my eyes.”

“I think nothing but count the seconds when I close my eyes.”

“When I closed my eyes I found myself in a dark world that is so lonely.”

Honest, but not terribly encouraging in terms of getting students to be creative, though perhaps the last one has possibilities.

In fairness, other students were somewhat more interesting...and psychotic:

“When I closed my eyes I imagine I was in a very beautiful world. In the world a river run through a bridge and to a grand castle. I was stood on the edge of the castle and looking to the end of the sky. Suddenly, a very huge and horrible devil was flying to my land, I picked up my sword and fight with the devil.”

Teaching English as a Second Language (ESL) at a school like this is a little like trying to get George Bush to use big words correctly. Even a well qualified team of “handlers” can expect a lot of repetitive exercises, some serious screw-ups and no shortage of “misunderestimated” frustration.

The system itself is self-defeating. As Tony put it only half-jokingly before he left: “student grade sheets have three columns—the student’s academic mark, their parent’s income and their final grade.” Cynical, but not far from the truth. Students who pay the tuition do not fail no matter how poorly they do academically. Students who never attend class and fail are given the opportunity to take a 5-minute makeup exam (oral) by a different teacher from the one who failed them, and if they survive that they pass the entire course. If they fail this makeup exam, the school still has the ultimate last word, and the kids are almost always passed. The system amounts to a pay-for-a-degree program requiring 4 years of tuition. Merit is not crucial. As a teacher, it can make you crazy.

In China failing the college entrance exam usually means not only no college but also a bad job...unless you can find a school like ours that, though not high on the academic totem pole, accepts students who cobble together the extravagant tuition and buy their way in. Ten-thousand yuan a year (about $1250 USD)–a small fortune for many Chinese—is the cost for one year at our school, compared with much lower fees at academically better, state-run institutions in big cities like Beijing, Tianjin or Nanjing.

Not all of the students here have rich parents. Some come from poor farming families who struggle immensely to send their kids to this college. It is to protect these students that we come down harder on the insolent kids that don’t apply themselves because they have never had to. I have kicked kids out of class in China for misbehavior, something I have never done in the U.S. It is necessary if you want to give the hard workers a chance—ones like the students who wrote these passages about their home life:

“In 2002 my father leaved home and drove a bus in a village. He began to live by himself with no good friends, no TV and no normal power. I think he often felt alone. He always went to bed at eight if the bus needn’t repair. He didn’t enjoy the Spring Festival with us for four years.

During this time [this year’s holiday] my sister and I went to the village. We accompanied our father to spend more happy time. I always help my father to wash the bus. If he will repair, I would help him at any moment. I didn’t talk a lot with my father [before this holiday], but we talk far more in Spring Festival. We talked about my future, the farm work, and the others. We changed different ideas, had a good talk. We are believed each other. We are understand each other. I think that was very important for this winter vacation. I have a good time in this Spring Festival because I spend more time with my father and help him do more work”

"First I miss my mother. She is very warm hearted even though she has the hot temper, but she loves me very much. She often told me something about what I should do. I miss her everyday. I miss my father too. There are four children in my family. My brother sister and I are students. Every day we cost so much. In order to let us study, my father work day and night. I think he is the great man in the world. I love and miss he very much. I can use word to express my feeling. Every day he told me study hard."

Also, unlike George Bush, many of the students are genuinely nice and it’s often the poorest students, the ones whose families are living hard so that their child can get a better education, that are the most generous and motivated. These are the students that make it worth trying to do a good job and these are the ones that say “welcome to my hometown” not to fill dead air, but because they are desperate to show you how they live and how generous their families can be.

“I was born in a poor village, 1980s. My family was poor, too. One day, it was dark but my parents still working hard on the farm. My sister and I couldn’t stay at home because there was no lights (our countryside was no electricity at that time). We were sitting at a corner of the ground of my house and crying. About half an hour past, my parents came back. They lighted the oil lighter. I saw their clothes was so broken, then I went to the corner and crying again. I pledged to be a useful man in the future. I must study hard.”

The educational system is much different in China than in the U.S. too (though increasingly we Americans also ‘teach to the test’). To some extent, one understands the predisposition for coasting among students who, as children, attend primary school from 7:30 a.m. until 5 p.m. and then stay up until 9 or 10 at night doing mandatory homework. College for many of these kids is a time to relax and have fun, far from the pressures of senior middle school (though they are often homesick).

My understanding of education in China is that students struggle through primary, junior and senior middle school in anticipation of the feared college entrance exam which is taken during their senior years. The entire system focuses on preparing the kids for a battery of standardized tests that they take periodically throughout their school years. It’s no wonder that kids are sick of study by the time they reach college. As one of our Chinese friends here put it (while her 10-year old studied), “nobody here likes the system but nobody changes it.”

One student described school life like this:

“Many years ago when I still studied in primary school, I lived through a very ‘hard life.’ Because my mother was a severe person and my father was more severe than her.

Therefore, they told me the first thing when I back home from school is study. I must have good scores on the exam, otherwise I would be blamed. So I had few time to play with my friends.

One day, my father taught me Chinese pinyin. I read it ‘p,’ but my father said the opposite so he thought it was “b.” So he yelled to me. ‘So fool mistake.’ I was so sad and cried. Fortunately my mother found the reason and told my father. After a few minutes silence, my father told me: ‘you can play all day.’

That day was one of my happiest days in my childhood.

China’s educational philosophy hinges on the importance of rote knowledge frequently at the expense of individual problem solving and critical thinking. We jokingly refer to “the collective brain” in our classes where correct answers can be dredged out of the class as a whole, but few individual students do well on, say, a simple vocabulary test.

I read an article recently (I can’t recall where and I don’t have copy of it in my notes) that said that although Chinese students often excel at math and science in school, they fail to achieve a proportionate level of success in their careers (for example publishing in prestigious journals, winning Nobel prizes, etc.) because, the article surmised, on the whole they lack the creativity and independence in their thinking that leads research in new directions and bears professional fruit.

Peter Hessler, in his book “River Town” describing his experience teaching in Sichuan in 1996, was frustrated by the lack of individual thought regarding the then impending return of Hong Kong to China. Paradoxically, he discovered that uneducated people in Fuling, where he taught, were more likely to have an original point of view than his better educated students:

“Two or three times a week I stopped to chat with Ke Xianlong, the forty-seven-year-old photographer in South Mountain Gate Park, and the more I got to know him the more I was surprised at his political views. He was completely uneducated but he had interesting ideas; sometimes he talked about the need for more democracy and other political parties, and these were views I never heard on campus...

I realized that as a thinking person his advantage lay precisely in his lack of formal education. Nobody told him what to think, and thus he was free to think clearly.

It wasn’t the sort of revelation that inspires a teacher. The more I thought about this, the more pessimistic I was about the education that my students were receiving, and I began to feel increasingly ambivalent about teaching in a place like that...”

There are blackboards outside of the classroom buildings on our campus where each semester students from different classes (students pass through college as a member of a single class of 35-60 students that take all of the same classes together) paint or use colored chalk to express themselves on whatever topics they choose (and they choose some odd topics). Ironically this semester, outside of the main classroom building, a class insightfully (or randomly??) chose the lyrics from “Nowhere Man” for their board:

He's a real nowhere man,

Sitting in his nowhere land,

Making all his nowhere plans

for nobody.

Doesn't have a point of view,

Knows not where he's going to,

Isn't he a bit like you and me?

After a hard day in class trying to get students to actually debate two sides of a topic, this message brings a bit of wry comical relief.

The Nowhere Man class chalkboard outside one of the classroom buildings.

Sometimes the lack of critical thinking can be infuriating. In response to a midterm exam question asking whether students thought that gay marriage should be allowed in China, one of my students wrote (unfortunately, I don’t have the exact quotation) that China is very susceptible to fashion trends and that since being gay might be seen as fashionable, if gay marriage were allowed all Chinese might decide to become gay, thereby ensuring the demise of China since there would be no next generation (because gays can’t have children).

I’m not kidding. That was from a 20-something-year-old second-year college student on a midterm exam.

Hessler, who usually had an admirably optimistic attitude about his teaching, wrote:

“...I realized that I was not teaching forty-five individual students with forty-five individual ideas. I was teaching a group, and these were moments when the group thought as one, and a group like that was a mob, even if it was silent and passive.”

So teaching here is a daily struggle between a sense of ineffectiveness and frustration on the one hand and responsibility to the twenty percent or so of the students who are motivated to learn on the other. For Ellen and me, being here is enough of a reward and teaching is the price we pay, so we make of it what we can. There are good days and bad days. As students have said in "position" papers: “every sword has two blades.” (??!!)

Ellen writes on the blackboard with self-destructing chalk. In a two hour class one typically uses 10-15 pieces of chalk.

And in truth, though it’s fun to wax cynical, I’m not complaining. Really. Each foreign teacher at our college is responsible for 14 classroom hours per week. For me that means five two-hour Oral English courses for non-English majors and two two-hour writing courses for English majors—altogether about 350 students. The writing courses are fun, and I feel like I accomplish something with the students, who are more motivated than the non-English majors. In the end, it amounts to only a 20-25 hour work week with lots of free time. Not at all a bad way to reside in a place like northern Yunnan, where a 2-hour bike ride can take you through villages that people fly halfway around the world to see.

And when we feel the most cynical, we go back and read what these nineteen to twenty-year-old kids write, sometimes for the humorous mistakes but more often to remind ourselves about how amazingly comfortable our lives are in the U.S., while much of the rest of the world still struggles.

Dear Ellen,

I’m Kid. Glad to write to you.

I’ve come [been] here for one month. I thought everything [would be] here, including my future. But the fact make me feel intimidate.

I come from a small village. You know, most of villages in China are not very well. As many students, I used to work on the farm for few years. There are only ten boys got access to the college for their future education in our country [region] this September. As a lucky dog, I felt very happy. But after a month’s classes I found that many students were not very serious with the study and their English was very poor. What a bad luck! Luckily, I am not the one in them. After a six years study I have learned most of the basic grammar, words (few) we use everyday.

You know, learning a foreign language is difficult for a foreigner. Like you and me. But now I think I have hope. Because I meet you. The God is great. He arrange us meet here.

So I will not quit.